ORGANISMS

CORONAVIRUS

IMF. June 4, 2020. IMF COUNTRY FOCUS. Sweden: Will COVID-19 Economics be Different?

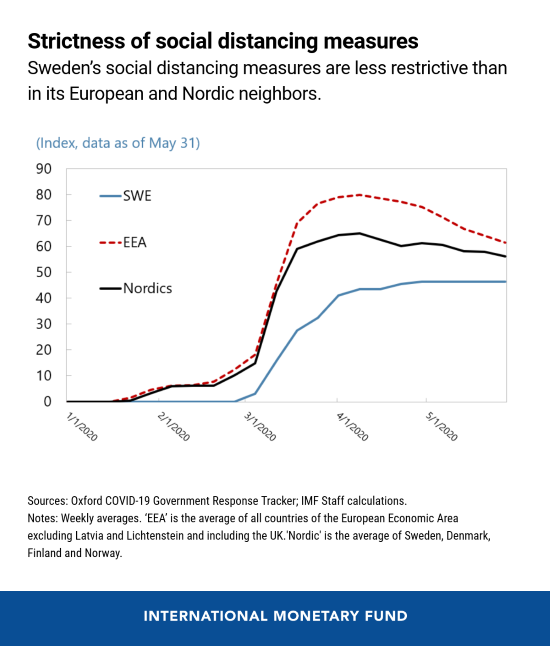

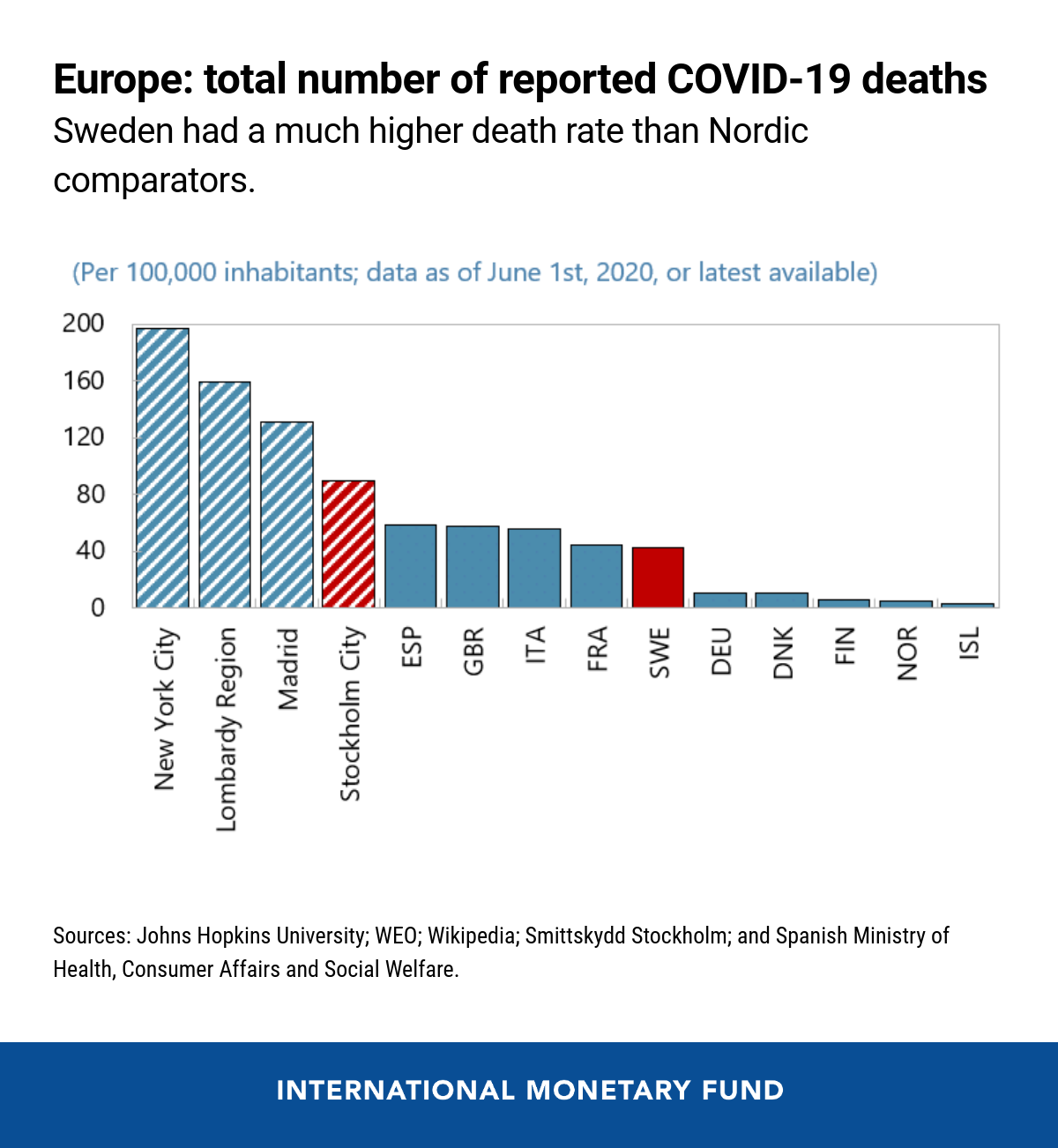

Sweden’s less restrictive containment strategy may have resulted in a milder economic contraction at the onset of the crisis, but uncertainty remains about its implications for the rest of the year. Other factors, including falling external demand, will heavily weigh on growth. Concerns have also been raised about the country’s death rate which, although lower than in Europe’s worst-affected countries, is a multiple of its Nordic neighbors.

In this article written for IMF Country Focus, the IMF's Sweden team* explains that the merits of Sweden’s strategy to contain COVID-19—which is based more on recommendations and social responsibility than legal obligations—are increasingly attracting attention, both from a health and an economic perspective.

The rationale for choosing this less restrictive approach was the view that the pandemic would last a long time.

Therefore, measures need to be socially and economically sustainable, while also keeping infection rates at a level that the Swedish health system can handle. The latter objective seems to have been achieved. However, the death toll so far has been relatively high.

Deaths have been concentrated along demographic, geographic, and socioeconomic lines: 50 percent of deaths occurred in elderly care facilities, and the 70+ age group accounted for almost 90 percent of all deaths.

In addition, greater Stockholm accounts for 50 percent of the deaths, with areas that have a higher share of persons that are foreign-born or have foreign-born parents being more heavily affected. This highlights the challenge of protecting the vulnerable in the absence of a more stringent lockdown, even in a country with favorable socio-demographic characteristics, including a very high share of single-person households. The outcome could have been worse in countries with different demographics, resources, or history of abiding by social contracts.

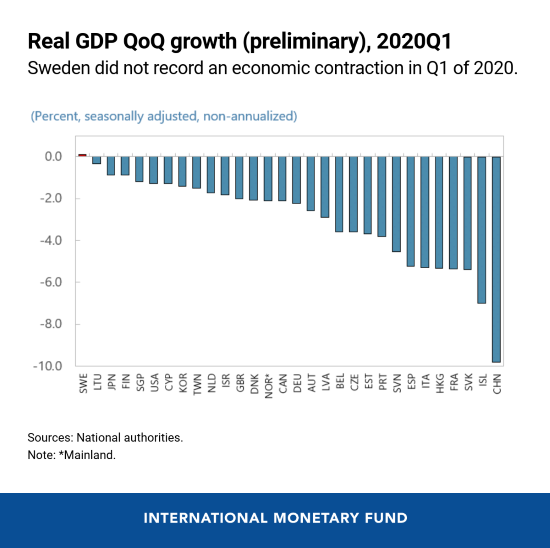

Sweden’s approach may have moderated the economic impact at the onset of the crisis, as indicated by the small increase in GDP for the first quarter of 2020 contrary to other advanced economies. Consumption declined less than in other countries, and exports temporarily increased.

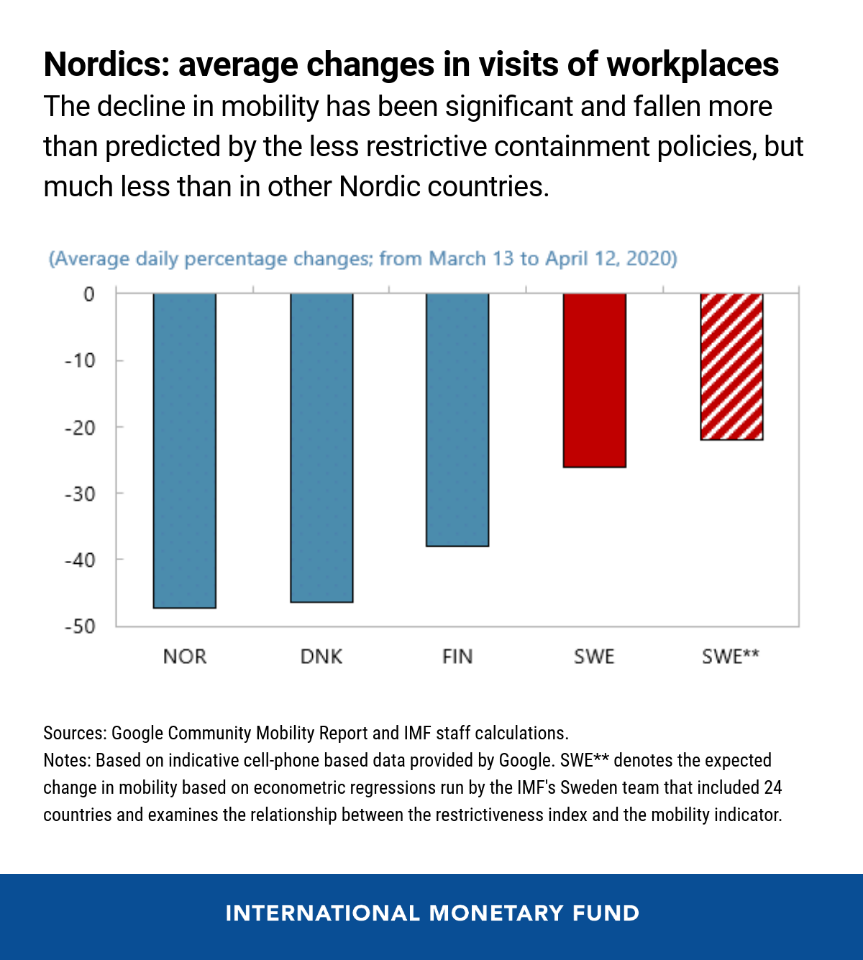

There was also a significant difference in people moving around, based on data from cell phones: The decline in mobility in Sweden was less than in other Nordic countries. However, visits to workplaces appear to have fallen more than predicted by the less restrictive containment policies.

This suggests that voluntary changes in behavior can play an important role, irrespective of regulations. However, while mobility does reflect economic activity to some degree, there are various other factors that affect the latter.

Domestic containment policies have a greater bearing on domestic demand, and particularly on non-tradeable—such as services—rather than tradeable sectors. The purchasing managers index (PMI) and other indicators that capture the perspectives on the economic outlook at the sectoral level appear to confirm that. The decline in service activity in Sweden between February and April, although significant, was much less than among European peers.

Swedish manufacturing, which is export-oriented, has also been hit hard: the fall in the manufacturing PMI in Sweden that started in March was in line with what other European countries are experiencing. This reflects a drop in external demand as well as supply chain disruptions, which are not determined by the country’s own containment policy.

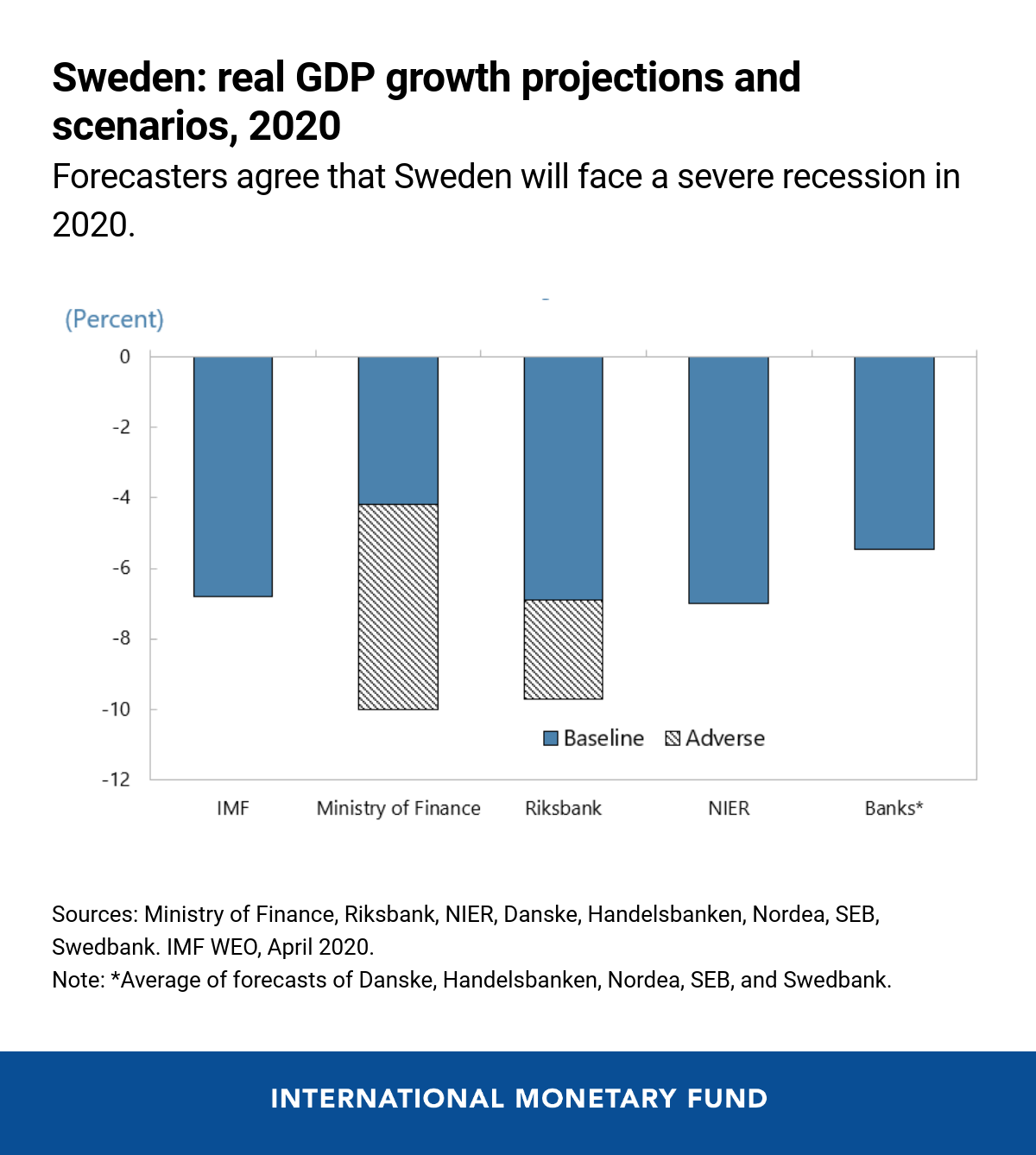

Together, these factors, and the relatively large fall in employment in recent weeks suggest the containment strategy may affect quarterly GDP growth rather than the outcome for the year as a whole. Most forecasters agree that Sweden will face a severe recession this year, but it is too early to say whether this strategy will prolong the recession or aid the recovery.

Any final verdict will also depend on whether, as a by-product of its approach, Sweden is closer to achieving herd immunity, thereby increasing its resilience in the event of another wave of infection. Medical knowledge about Covid-19 is still accumulating, and recent tests indicate that immunity gains have been lower than initially projected.

Irrespective of the containment strategy, swift decisive macroeconomic policy action remains critical to avert more dire economic outcomes. Sweden’s policy response to combat the economic impact of the pandemic has been prompt, large, and well-designed. This highlights the importance of having built up ample fiscal space, and of preserving the operational independence of the central bank (Riksbank), enabling it to quickly deploy a broad menu of instruments.

* IMF mission team members: Jana Bricco, Florian Misch, Khaled Sakr, and Alexandra Solovyeva.

FULL DOCUMENT: https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/06/01/na060120-sweden-will-covid-19-economics-be-different?utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery

IMF. May 28, 2020. IMF COUNTRY FOCUS. Jamaica Ramps Up Social and Economic Support in COVID-19 Response. The COVID-19 pandemic is hurting Jamaica’s tourism industry

The COVID-19 crisis is having a significant impact on Jamaica. The pandemic, which is severely hurting tourism and remittances, reached the Caribbean country just a few months after the successful conclusion of its economic reform program—which was supported by a $1.66 billion Stand-By Arrangement from the IMF.

In response, the government has ramped up its recovery efforts and established a special task force to effectively respond to the economic impact of the crisis. In this context, Jamaica has also requested emergency financing from the IMF in the amount of $520 million.

In an interview with IMF Country Focus, Jamaica’s Minister of Finance and the Public Service, Nigel Clarke, explains what measures the country is taking to protect lives and livelihoods from the impact of the pandemic.

What has been the economic impact of COVID-19 on Jamaica?

As with most economies around the world, the Jamaican economy has been significantly impacted by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. The economy is expected to contract by over 5 percent this fiscal year. Furthermore, government revenues are expected to decline by double digits even as emergency health expenditures as well as social and economic support expenditures rise.

Our balance of payments will also be negatively impacted by our considerably lower inflows from tourism and remittances, which prior to the pandemic represented approximately 20 and 15 percent of GDP, respectively. As such, the COVID-19 pandemic is having a multi-dimensional impact.

What economic measures has Jamaica taken so far to combat the effects of the pandemic?

The government implemented a social and economic support program called the CARE Programme, which provides assistance to vulnerable individuals and small businesses through innovative and existing delivery channels.

More specifically, the program provides:

- compassionate grants to those who were unemployed or informally employed pre-pandemic;

- temporary unemployment benefits to the previously employed who have been laid off or terminated since the pandemic; and

- grants to the self-employed whose regular earnings have been disrupted in addition to grants to small businesses.

The CARE Programme also incentivizes employers in targeted sectors to remain connected to their employees. Transfers are made to businesses that retain employees (who are below a particular income level) on their payroll. Among other measures, the CARE Programme provides support for the sick, the elderly, the disabled, and those who were economically vulnerable pre-pandemic by supplementing existing programs.

In addition, we have supported new health expenditures. The fiscal year 2020/21 budget is being adjusted to accommodate lower revenues, new expenditures, re-prioritizing of previously planned expenditures, and utilization of cash resources.

It is also worth noting that, even during these unprecedented times, the government has taken, and will continue to take, steps to ensure transparency and good governance in spending and procurement associated with our COVID-19 policy responses. For example, we plan to publish key information on procurement contracts and, as we have already done with the CARE Programme, will request that the Auditor General’s Department undertake and publish an audit of COVID-19 related spending.

Jamaica’s strong ownership throughout its economic program and track record implementing reforms resulted in a stronger and more resilient economy. How have these reforms helped during this challenging time?

The most obvious way is that we have encountered the pandemic with significantly lower debt than we had when we entered the global financial crisis ten years ago. This has provided some flexibility.

In addition, we had accumulated cash resources of over 3 percent of GDP through public body reform, inclusive of divestment of state enterprises, and fiscal over-performance. We were planning to use these resources to accelerate debt repayment.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, however, we will instead need to draw down on these resources to assist in financing budgetary expenditures in light of the decline in revenues and the new emergency expenditures that have arisen. The reforms that gave rise to these cash resources have put Jamaica in a much stronger position with a wider pool of options.

Finally, Jamaica’s monetary policy framework was strengthened over the course of the Stand-By Arrangement with price stability becoming the central goal of monetary policy under a flexible exchange rate regime. This allowed for significant reserve accumulation with non-borrowed net international reserves increasing by over $1 billion. Work continues to further develop foreign exchange and debt markets, which will be critical in sustaining an efficient intermediation of capital to support increased investment in Jamaica.

How has the ongoing work in developing the Natural Disaster Risk Management policy framework helped in responding to the COVID-19 shock?

We made a historic transfer to our Natural Disaster Contingencies Fund, which was created to provide for unforeseen disaster-related expenditures of any kind two fiscal years ago. We were able to draw down from this contingency to finance some of the emergency social spending.

It was extremely useful to have this option. The amount drawn will be replaced as part of the appropriation process. However, we would not have been able to respond to the COVID-19 related emergencies as quickly and as nimbly as we did without the resources available in the Natural Disaster Contingencies Fund.

How will Jamaica make use of the emergency assistance from the Rapid Financing Instrument?

Given the severe shock from the pandemic, the proceeds of the Rapid Financing Instrument will be used to strengthen the reserves at the Bank of Jamaica. As of now, we do not need the financing facility for budgetary support. We are using our own cash resources and other programmed budgetary inflows.

FULL DOCUMENT: https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/05/27/na052720-jamaica-ramps-up-social-and-economic-support-in-covid-19-response?utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery

IMF. November 7, 2019. Jamaica: On the Path to Higher Economic Growth

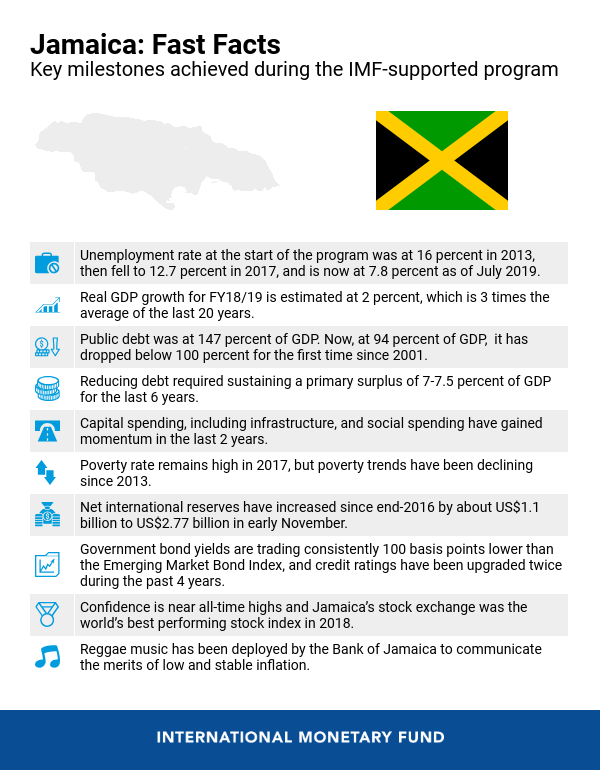

Jamaica has successfully concluded its economic reform program, which was supported by a US$1.66 billion Stand-By Arrangement from the IMF. The country’s strong ownership, as well as the government’s steadfast reform implementation have resulted in a stronger economy, an all-time low unemployment rate, and a significant reduction in public debt.

In an interview with Uma Ramakrishnan, former head of the IMF team for Jamaica, we discuss the history, evolution, and achievements of the recently-concluded program.

How would you describe Jamaica’s economy before the program?

Prior to the IMF-supported programs, Jamaica’s economy suffered from years of very low growth. This was combined with high and unsustainable public debt of about 145 percent of GDP, which was accumulated over several decades of weak policy implementation.

High borrowing needs to finance public debt led to financial repression—the use of various measures to channel funds to the government—and crowded out private sector credit and investment. These high debt servicing costs limited room in the government’s budget and inhibited spending on critical needs of the Jamaican people—like infrastructure and social assistance. A weak external position was reflected in a current account deficit of around 12 percent of GDP, and low net international reserves of around US$0.9 billion in 2012.

And how is Jamaica’s economy now?

The key goals under the two successive IMF-supported programs were to restore economic stability, while pursuing policies that will provide a long-term foundation to sustain growth, create jobs, and protect the most vulnerable. Since the start of the 2013 Extended Fund Facility and the subsequent precautionary Stand-By Arrangement in 2016, Jamaica’s public debt has fallen by about 50 percent of GDP and is on track to reach the legislated 60 percent of GDP target by FY25/26.

The unemployment rate—at about 7.8 percent—is at an all-time low. Both the current account deficit and inflation are subdued, and foreign reserves have been rebuilt to comfortable levels. In addition, monetary policy is on track to bring inflation to the mid-point of the Bank of Jamaica’s target band. Growth has improved—supported by mining, construction, and agriculture industries but the outlook is weaker than envisioned at the start of the programs, and poverty remains high.

To follow up, now that the program has ended, is there a risk that remaining reforms will go unfinished?

We are confident that there is still momentum and commitment to continue reforms in several key areas to support broad-based and higher growth. This includes completing the work on building domestic institutions, such as a fiscal council, an independent central bank, a disaster financing policy framework, and a well-functioning governance framework for public bodies.

Moreover, a meaningful transformation of the public sector that prioritizes government functions and redesigns public sector compensation needs to be at the top of the government’s agenda. This should help create room for fiscal policy to tackle growth impediments such as the large infrastructure and skills gap; high crime; low financial access and inclusion; and an inadequate social safety net.

Can you talk more about what contributed to the program’s successful completion?

A big reason for the success of the economic reform program in Jamaica resulted from the power of ownership. For instance, there was strong bipartisan support for fiscal discipline, and the social consensus to sustain it.Various stakeholders—for example, private and public sectors, civil society, unions—got behind the reforms across two administrations.

That social partnership for change and the championing and monitoring of reform commitments by the Economic Programme Oversight Committee (EPOC) was a critical force, which will need to continue to tackle the deep-rooted structural issues. In addition, phasing-in difficult reforms was critical (for example, the switch from direct to indirect taxes, increasing public employees’ pension contributions, and central bank recapitalization were all done over multiple years).

Going forward, how do you see the partnership between Jamaica and the IMF evolving?

First and foremost, the strong partnership between Jamaica and the Fund will continue through our regular economic health checks and capacity development—that is well-tailored for Jamaica, as it was under the program. More specifically, technical assistance to support economic and fiscal capacity building, foreign exchange and capital market development, and risk-based supervision are ongoing. Jamaica’s Resident Representative’s office will also remain open for two additional years to help coordinate these efforts and ensure that the authorities’ needs are being met.

FULL DOCUMENT: https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2019/11/07/NA110719-Jamaica-On-the-Path-to-Higher-Economic-Growth?utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery

___________________

US ECONOMICS

CORONAVIRUS / ECONOMY RECOUVERING

THE WHITE HOUSE. Council of Economic Advisers. June 5, 2020. ECONOMY & JOBS. Trouncing Expectations by 10 Million Jobs, the Labor Market’s Comeback Has Begun

The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ May Employment Situation report shows that the United States economy added 2.5 million jobs last month, and the unemployment rate fell from 14.7 percent to 13.3 percent.

Employment increased significantly in leisure and hospitality (1.2 million), construction (464,000), education and health services (424,000), retail trade (368,000), and manufacturing (225,000). These job gains surprised forecasters, given many States were only beginning to reopen their economies during the reports’ survey reference periods (the week/pay period that includes May 12). The median of all private sector forecasts predicted 7.5 million job losses in May and an unemployment rate of 19.2 percent.

Rapid job growth as the coronavirus is contained and States open up should not come as a surprise. A poll conducted from April 27 through May 4 asked laid-off workers if they expected to be rehired by their most recent employers after State stay-at-home orders are lifted. The vast majority of laid-off workers (77 percent) said it was likely that they would be rehired by their most recent employers. This survey result is echoed in May’s employment data, just as CEA explained it was in April’s data.

There were 15.3 million people on temporary layoff in May, in addition to an estimated 4.9 million people who had temporarily lost their jobs but were counted as employed but “not at work for other reasons.” Including all those who were potentially on temporary layoff, 78.2 percent of unemployed persons in May were on temporary layoff—well above the 13.3 percent average over the 12 months before this March.

Beyond workers remaining attached to their employers, another sign that job growth will continue is May’s jump in average weekly hours—indicating pent-up demand. Increasing hours can be a sign that employers need to hire more workers to meet this demand. For all private sector employees, average weekly hours increased by 0.5 to 34.7 hours—the highest level since the series began in 2006. For production and non-supervisory employees, this measure increased by 0.6 to 34.1 hours—the highest level in 19 years.

Further job losses were expected in the May report because initial Unemployment Insurance (UI) claims, though falling, remain elevated. Yesterday, the Department of Labor reported that 1.9 million people filed initial UI claims in the week ending May 30. Even with 4.6 million initial claims over the two weeks ending May 23, the number of people receiving UI, as measured by continuing claims, declined by 3.4 million over that time. As the figure below shows, weekly continuing claims have tracked the number of unemployed persons reported in the monthly Employment Situation report, assuming a constant rate of change between the months.

By May 23, the gap between weekly continuing claims and cumulative initial UI claims since the beginning of COVID-related job losses had grown to 19.6 million. Some of this difference may be accounted for by individuals applying for traditional UI instead of the new Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program, either by mistake or because of State requirements. However, the widening gap between initial UI claims and continuing claims, along with the 2.5 million jobs added in May, show that laid off Americans are returning to work.

For workers to count as unemployed, they must have searched for work during the last four weeks or be on temporary layoff. If neither of these apply, the worker is counted as out of the labor force. States waived the traditional work search requirement for UI, so some workers on UI who do not expect to be called back to work may not count as unemployed. Yet the labor market flows for May show that there was not an elevated level of workers dropping out of the labor force directly. Flows from employment to not in the labor force were 4.4 million from April to May, in line with the average over the 12 months before this March (4.7 million). Furthermore, from April to May, 2.8 million more people moved from unemployment to employment than moved from employment to unemployment.

Other, more rapid indicators of labor market strength show the economic recovery has accelerated since mid-May. Gasoline demand has recovered over half of the loss from its pandemic-low, indicating Americans are driving more. Workplace visits are up more than 40 percent from its pandemic-low. And, as the figure below shows, 73 percent of small businesses are now open—up from its pandemic-low of 52 percent right before the April report’s reference periods.

While May’s jobs report is unquestionably positive news for America’s economic comeback, there is still much more room to grow. Three months ago in February, the unemployment rate was 9.8 percentage points lower (3.5 percent) and there were 19.6 million more jobs. But the economy beating expectations by 10 million jobs and the unemployment rate falling instead of rising show that the transition back to strong economic growth began earlier than many expected. With more States easing restrictions on work, strong attachments between laid off workers and their employers, and growing labor demand, there is much reason to expect the American economy to add even more jobs in June.

FULL DOCUMENT: https://www.whitehouse.gov/articles/trouncing-expectations-10-million-jobs-labor-markets-comeback-begun/

THE WHITE HOUSE. June 4, 2020. INFRASTRUCTURE AND TECHNOLOGY. EXECUTIVE ORDERS. EO on Accelerating the Nation’s Economic Recovery from the COVID-19 Emergency by Expediting Infrastructure Investments and Other Activities

By the authority vested in me as President by the Constitution and the laws of the United States of America, I hereby determine and authorize as follows:

Section 1. Purpose. The 2019 novel coronavirus known as SARS-CoV-2, the virus causing outbreaks of the disease COVID-19, has significantly disrupted the lives of Americans. In Proclamation 9994 of March 13, 2020 (Declaring a National Emergency Concerning the Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Outbreak), I declared, pursuant to the National Emergencies Act, 50 U.S.C. 1601 et seq., that the COVID-19 outbreak in the United States constituted a national emergency that posed a threat to our national security (“the national emergency”). I also determined that same day that the COVID-19 outbreak constituted an emergency of nationwide scope, pursuant to section 501(b) of the Stafford Act (42 U.S.C. 5191(b)).

Since I declared this national emergency, the American people have united behind a policy of mitigation strategies, such as social distancing, to reduce the spread of COVID-19. The unavoidable result of the COVID-19 outbreak and these necessary mitigation measures has been a dramatic downturn in our economy. National unemployment claims have reached historic levels. In the days between the national emergency declaration and May 23, 2020, more than 41 million Americans filed for unemployment, and the unemployment rate reached 14.7 percent. In light of this and other developments, I have determined that, without intervention, the United States faces the likelihood of a potentially protracted economic recovery with persistent high unemployment.

From the beginning of my Administration, I have focused on reforming and streamlining an outdated regulatory system that has held back our economy with needless paperwork and costly delays. Antiquated regulations and bureaucratic practices have hindered American infrastructure investments, kept America’s building trades workers from working, and prevented our citizens from developing and enjoying the benefits of world-class infrastructure.

The need for continued progress in this streamlining effort is all the more acute now, due to the ongoing economic crisis. Unnecessary regulatory delays will deny our citizens opportunities for jobs and economic security, keeping millions of Americans out of work and hindering our economic recovery from the national emergency.

In tandem with this regulatory reform, I will continue to use existing legal authorities to respond to the full dimensions of the national emergency and its economic consequences. These authorities include statutes and regulations that allow for expedited government decision making in exigent circumstances.

Sec. 2. Policy. Agencies, including executive departments, should take all appropriate steps to use their lawful emergency authorities and other authorities to respond to the national emergency and to facilitate the Nation’s economic recovery. As set forth in this order, agencies should take all reasonable measures to speed infrastructure investments and to speed other actions in addition to such investments that will strengthen the economy and return Americans to work, while providing appropriate protection for public health and safety, natural resources, and the environment, as required by law. For purposes of this order, the term “agencies” has the meaning given that term in section 3502(1), of title 44, United States Code, except for the agencies described in section 3502(5) of title 44.

Sec. 3. Expediting the Delivery of Transportation Infrastructure Projects. (a) To facilitate the Nation’s economic recovery, the Secretary of Transportation shall use all relevant emergency and other authorities to expedite work on, and completion of, all authorized and appropriated highway and other infrastructure projects that are within the authority of the Secretary to perform or to advance.

(b) No later than 30 days of the date of this order, the Secretary of Transportation shall provide a summary report, listing all projects that have been expedited pursuant to subsection (a) of this section (“expedited transportation projects”), to the Director of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), the Assistant to the President for Economic Policy, and the Chairman of the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ). Such report may be combined, as appropriate, with any other reports required by this order.

(c) Within 30 days following the submission of the initial summary report described in subsection (b) of this section, the Secretary of Transportation shall provide a status report to the OMB Director, the Assistant to the President for Economic Policy, and the Chairman of CEQ that shall list any additions or other changes to the list described in subsection (b) of this section. Such status reports shall thereafter be provided to these officials at least every 30 days for the duration of the national emergency, and may be combined, as appropriate, with any other reports required by this order.

Sec. 4. Expediting the Delivery of Civil Works Projects Within the Purview of the Army Corps of Engineers. (a) To facilitate the Nation’s economic recovery, the Secretary of the Army, acting through the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Civil Works, shall use all relevant emergency and other authorities to expedite work on, and completion of, all authorized and appropriated civil works projects that are within the authority of the Secretary of the Army to perform or to advance.

(b) No later than 30 days of the date of this order, the Secretary of the Army, acting through the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Civil Works, shall provide a summary report, listing all such projects that have been expedited (“expedited Army Corps of Engineers projects”), to the OMB Director, the Assistant to the President for Economic Policy, and the Chairman of CEQ. Such report may be combined, as appropriate, with any other reports required by this order.

(c) Within 30 days following the submission of the initial summary report described in subsection (b) of this section, the Secretary of the Army, acting through the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Civil Works, shall provide a status report to the OMB Director, the Assistant to the President for Economic Policy, and the Chairman of CEQ. Each such report shall list the status of all expedited Army Corps of Engineers projects and shall list any additions or other changes to the list described in subsection (b) of this section. Such status reports shall thereafter be provided to these officials at least every 30 days for the duration of the national emergency and may be combined, as appropriate, with any other reports required by this order.

Sec. 5. Expediting the Delivery of Infrastructure and Other Projects on Federal Lands. (a) As used in this section, the term “Federal lands” means any land or interests in land owned by the United States, including leasehold interests held by the United States, except Indian trust land.

(b) To facilitate the Nation’s economic recovery, the Secretary of Defense, the Secretary of the Interior, and the Secretary of Agriculture shall use all relevant emergency and other authorities to expedite work on, and completion of, all authorized and appropriated infrastructure, energy, environmental, and natural resources projects on Federal lands that are within the authority of each of the Secretaries to perform or to advance.

(c) No later than 30 days of the date of this order, the Secretary of Defense, the Secretary of the Interior, and the Secretary of Agriculture shall each provide a summary report, listing all such projects that have been expedited (“expedited Federal lands projects”), to the OMB Director, the Assistant to the President for Economic Policy, and the Chairman of CEQ. Such report may be combined, as appropriate, with any other reports required by this order.

(d) Within 30 days following the submission of the initial summary report described in subsection (c) of this section, the Secretary of Defense, the Secretary of the Interior, and the Secretary of Agriculture shall each provide a status report to the OMB Director, the Assistant to the President for Economic Policy, and the Chairman of CEQ. Each such report shall list the status of all expedited Federal lands projects and shall list any additions or other changes to the list described in subsection (c) of this section. Such status reports shall thereafter be provided to these officials at least every 30 days for the duration of the national emergency and may be combined, as appropriate, with any other reports required by this order.

Sec. 6. National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) Emergency Regulations and Emergency Procedures. The Council on Environmental Quality has provided appropriate flexibility to agencies for complying with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), 42 U.S.C. 4321 et seq., in emergency situations. Such flexibility is expressly authorized in CEQ’s regulations, contained in title 40, Code of Federal Regulations, that implement the procedural provisions of NEPA (the “NEPA regulations”), which were first issued in 1978. These regulations provide that when emergency circumstances make it necessary to take actions with significant environmental impacts without observing the regulations, agencies may consult with CEQ to make alternative arrangements to take such actions. Using this authority, CEQ has appropriately approved alternative arrangements in a wide variety of pressing emergency situations. These emergencies have included not only natural disasters and threats to the national defense, but also threats to human and animal health, energy security, agriculture and farmers, and employment and economic prosperity.

(a) No later than 30 days of the date of this order, the heads of all agencies:

(i) shall identify planned or potential actions to facilitate the Nation’s economic recovery that:(b) To facilitate the Nation’s economic recovery, the heads of all agencies are directed to use, to the fullest extent possible and consistent with applicable law, emergency procedures, statutory exemptions, categorical exclusions, analyses that have already been completed, and concise and focused analyses, consistent with NEPA, CEQ’s NEPA regulations, and agencies’ NEPA procedures.(A) may be subject to emergency treatment as alternative arrangements pursuant to CEQ’s NEPA regulations and agencies’ own NEPA procedures;(ii) shall provide a summary report, listing such actions, to the OMB Director, the Assistant to the President for Economic Policy, and the Chairman of CEQ. Such report may be combined, as appropriate, with any other reports required by this order.

(B) may be subject to statutory exemptions from NEPA;

(C) may be subject to the categorical exclusions that agencies have included in their NEPA procedures pursuant to the NEPA regulations;

(D) may be covered by already completed NEPA analyses that obviate the need for new analyses; or

(E) may otherwise use concise and focused NEPA environmental analyses; and

(c) Within 30 days following the submission of the initial summary report described in subsection (a)(ii) of this section, each agency shall provide a status report to the OMB Director, the Assistant to the President for Economic Policy, and the Chairman of CEQ. Each such report shall list actions taken within the categories described in subsection (a)(i) of this section, shall list the status of any previously reported planned or potential actions, and shall list any new planned or potential actions within these categories. Such status reports shall thereafter be provided to these officials at least every 30 days for the duration of the national emergency and may be combined, as appropriate, with any other reports required by this order.

(d) The Chairman of CEQ shall be available to consult promptly with agencies and to take other prompt and appropriate action concerning the application of CEQ’s NEPA emergency regulations.

Sec. 7. Endangered Species Act (ESA) Emergency Consultation Regulations. (a) No later than 30 days of the date of this order, the heads of all agencies:

(i) shall identify planned or potential actions to facilitate the Nation’s economic recovery that may be subject to the regulation on consultations in emergencies, see 50 C.F.R. 402.05, promulgated by the Secretary of the Interior and the Secretary of Commerce pursuant to the Endangered Species Act (ESA), 16 U.S.C. 1531 et seq.; and

(ii) shall provide a summary report, listing such actions, to the Secretary of the Interior, the Secretary of Commerce, the OMB Director, the Assistant to the President for Economic Policy, and the Chairman of CEQ. (The Secretary of the Interior and the Secretary of Commerce shall provide such summary reports, listing such actions on behalf of their respective agencies, to each other and for internal use throughout their respective agencies, as well as to the OMB Director, the Assistant to the President for Economic Policy, and the Chairman of CEQ.) Such report may be combined, as appropriate, with any other reports required by this order.(b) The heads of all agencies are directed to use, to the fullest extent possible and consistent with applicable law, the ESA regulation on consultations in emergencies, to facilitate the Nation’s economic recovery.

(c) Within 30 days following the submission of the initial summary report described in subsection (a)(ii) of this section, the head of each agency shall provide a status report to the Secretary of the Interior, the Secretary of Commerce, the OMB Director, the Assistant to the President for Economic Policy, and the Chairman of CEQ. (The Secretary of the Interior and the Secretary of Commerce shall provide such status reports, listing such actions on behalf of their respective agencies, to each other and for internal use throughout their respective agencies, as well as to the OMB Director, the Assistant to the President for Economic Policy, and the Chairman of CEQ.) Each such report shall list actions taken within the categories described in subsection (a)(i) of this section, shall list the status of any previously reported planned or potential actions, and shall list any new planned or potential actions within these categories. Such status reports shall thereafter be provided to these officials at least every 30 days for the duration of the national emergency and may be combined, as appropriate, with any other reports required by this order.

(d) The Secretary of the Interior shall ensure that the Director of the Fish and Wildlife Service, or the Director’s authorized representative, shall be available to consult promptly with agencies and to take other prompt and appropriate action concerning the application of the ESA’s emergency regulations. The Secretary of Commerce shall ensure that the Assistant Administrator for Fisheries for the National Marine Fisheries Service, or the Assistant Administrator’s authorized representative, shall be available for such consultation and to take such other action.

Sec. 8. Emergency Regulations and Nationwide Permits Under the Clean Water Act (CWA) and Other Statutes Administered by the Army Corps of Engineers. (a) No later than 30 days of the date of this order, the heads of all agencies, including the Secretary of the Army, acting through the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Civil Works:

(i) shall identify planned or potential actions to facilitate the Nation’s economic recovery that may be subject to emergency treatment pursuant to the regulations and nationwide permits promulgated by the Army Corps of Engineers, or jointly by the Corps and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), pursuant to section 404 of the Clean Water Act, 33 U.S.C. 1344, section 10 of the Rivers and Harbors Act of March 3, 1899, 33 U.S.C. 403, and section 103 of the Marine Protection Research and Sanctuaries Act of 1972, 33 U.S.C. 1413 (collectively, the “emergency Army Corps permitting provisions”); and

(ii) shall provide a summary report, listing such actions, to the Secretary of the Army, acting through the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Civil Works; the OMB Director; the Assistant to the President for Economic Policy; and the Chairman of CEQ. Such report may be combined, as appropriate, with any other reports required by this order.(b) The heads of all agencies are directed to use, to the fullest extent possible and consistent with applicable law, the emergency Army Corps permitting provisions, to facilitate the Nation’s economic recovery.

(c) Within 30 days following the submission of the initial summary report described in subsection (a)(ii) of this section, each agency shall provide a status report to the Secretary of the Army, acting through the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Civil Works; the OMB Director; the Assistant to the President for Economic Policy; and the Chairman of CEQ. Each such report shall list actions taken within subsection (a)(i) of this section, shall list the status of any previously reported planned or potential actions, and shall list any new planned or potential actions that fall within subsection (a)(i). Such status reports shall thereafter be provided to these officials at least every 30 days for the duration of the national emergency and may be combined, as appropriate, with any other reports required by this order.

(d) The Secretary of the Army, acting through the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Civil Works, shall be available to consult promptly with agencies and to take other prompt and appropriate action concerning the application of the emergency Army Corps permitting provisions. The Administrator of the EPA shall provide prompt cooperation to the Secretary of the Army and to agencies in connection with the discharge of the responsibilities described in this section.

Sec. 9. Other Authorities Providing for Emergency or Expedited Treatment of Infrastructure Improvements and Other Activities. (a) No later than 30 days of the date of this order, all heads of agencies:

(i) shall review all statutes, regulations, and guidance documents that may provide for emergency or expedited treatment (including waivers, exemptions, or other streamlining) with regard to agency actions pertinent to infrastructure, energy, environmental, or natural resources matters;

(ii) shall identify planned or potential actions, including actions to facilitate the Nation’s economic recovery, that may be subject to emergency or expedited treatment (including waivers, exemptions, or other streamlining) pursuant to those statutes and regulations; and

(iii) shall provide a summary report, listing such actions, to the OMB Director, the Assistant to the President for Economic Policy, and the Chairman of CEQ. Such report may be combined, as appropriate, with any other reports required by this order.(b) Consistent with applicable law, agencies shall use such statutes and regulations to the fullest extent permitted to facilitate the Nation’s economic recovery.

(c) Within 30 days following the submission of the initial summary report described in subsection (a)(iii) of this section, each agency shall provide a status report to the OMB Director, the Assistant to the President for Economic Policy, and the Chairman of CEQ. Each such report shall list actions taken within subsection (a)(ii) of this section, shall list the status of any previously reported planned or potential actions, and shall list any new planned or potential actions that fall within subsection (a)(ii). Such status reports shall thereafter be provided to these officials at least every 30 days for the duration of the national emergency and may be combined, as appropriate, with any other reports required by this order.

Sec. 10. General Provisions. (a) Nothing in this order shall be construed to impair or otherwise affect:

(i) the authority granted by law to an executive department or agency, or the head thereof; or

(ii) the functions of the OMB Director relating to budgetary, administrative, or legislative proposals.(b) This order shall be implemented consistent with applicable law and subject to the availability of appropriations.

(c) This order is not intended to, and does not, create any right or benefit, substantive or procedural, enforceable at law or in equity by any party against the United States, its departments, agencies, or entities, its officers, employees, or agents, or any other person.

FULL DOCUMENT: https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/eo-accelerating-nations-economic-recovery-covid-19-emergency-expediting-infrastructure-investments-activities/

__________________

LGCJ.: