US ECONOMICS

BRASIL

U.S. Department of State. 02/27/2020. Secretary Pompeo’s Call with Brazilian Foreign Minister Araujo

The below is attributable to Spokesperson Morgan Ortagus:

Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo spoke today with Brazilian Foreign Minister Ernesto Araujo regarding the upcoming visit of Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro to Miami. Secretary Pompeo and Foreign Minister Araujo discussed the importance of the close U.S.-Brazilian partnership in our efforts to promote democracy and economic prosperity in the region.

GDP

DoC. BEA. February 27, 2020. Gross Domestic Product, Fourth Quarter and Year 2019 (Second Estimate)

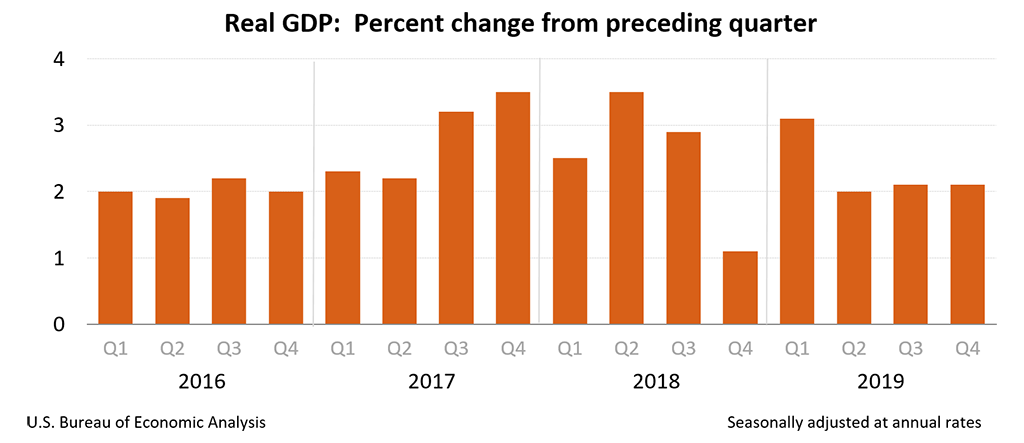

Real gross domestic product (GDP) increased at an annual rate of 2.1 percent in the fourth quarter of 2019 (table 1), according to the "second" estimate released by the Bureau of Economic Analysis. In the third quarter, real GDP also increased 2.1 percent.

The GDP estimate released today is based on more complete source data than were available for the "advance" estimate issued last month. In the advance estimate, the increase in real GDP was also 2.1 percent. In the second estimate, an upward revision to private inventory investment was offset by a downward revision to nonresidential fixed investment (see "Updates to GDP" on page 2).

Real GDP growth in the fourth quarter was the same as that in the third. In the fourth quarter, a downturn in imports and an acceleration in government spending were offset by a larger decrease in private inventory investment and a slowdown in PCE.

Current dollar GDP increased 3.5 percent, or $184.2 billion, in the fourth quarter to a level of $21.73 trillion. In the third quarter, GDP increased 3.8 percent, or $202.3 billion (tables 1 and 3).

The price index for gross domestic purchases increased 1.4 percent in the fourth quarter, the same increase as in the third quarter (table 4). The PCE price index increased 1.3 percent, compared with an increase of 1.5 percent. Excluding food and energy prices, the PCE price index increased 1.2 percent, compared with an increase of 2.1 percent.

More information on the source data that underlie the estimates is available in the "Key Source Data and Assumptions" file on BEA’s website.

Updates to GDP

In the second estimate, the fourth-quarter growth rate in real GDP was unrevised from the advance estimate. Private inventory investment, exports, federal government spending, and residential fixed investment were revised up. These upward revisions were offset by downward revisions to nonresidential fixed investment, PCE, state and local government spending, and an upward revision to imports. For more information, see the Technical Note and the "Additional Information" section below.

| Advance Estimate | Second Estimate | |

|---|---|---|

| (Percent change from preceding quarter) | ||

| Real GDP | 2.1 | 2.1 |

| Current-dollar GDP | 3.6 | 3.5 |

| Gross domestic purchases price index | 1.5 | 1.4 |

| PCE price index | 1.6 | 1.3 |

| PCE price index excluding food and energy | 1.3 | 1.2 |

For the third quarter of 2019, the percent change in real GDI was revised from 2.1 percent to 1.2 percent based on new third-quarter data from the BLS Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages.

2019 GDP

Real GDP increased 2.3 percent in 2019 (from the 2018 annual level to the 2019 annual level), compared with an increase of 2.9 percent in 2018 (table 1).

The increase in real GDP in 2019 reflected positive contributions from PCE, nonresidential fixed investment, federal government spending, state and local government spending, and private inventory investment that were partly offset by a negative contribution from residential fixed investment. Imports increased (table 2).

The deceleration in real GDP in 2019, compared to 2018, primarily reflected decelerations in nonresidential fixed investment and PCE, which were partly offset by accelerations in both state and local and federal government spending. Imports increased less in 2019 than in 2018.

Current-dollar GDP increased 4.1 percent, or $846.9 billion, in 2019 to a level of $21.43 trillion, compared with an increase of 5.4 percent, or $1,060.8 billion, in 2018 (tables 1 and 3).

The price index for gross domestic purchases increased 1.5 percent in 2019, compared with an increase of 2.4 percent in 2018 (table 4). The PCE price index increased 1.4 percent, compared with an increase of 2.1 percent. Excluding food and energy prices, the PCE price index increased 1.6 percent, compared with an increase of 1.9 percent (table 4).

Measured from the fourth quarter of 2018 to the fourth quarter of 2019, real GDP increased 2.3 percent during the period. That compared with an increase of 2.5 percent during 2018. The price index for gross domestic purchases, as measured from the fourth quarter of 2018 to the fourth quarter of 2019, increased 1.4 percent during 2019. That compared with an increase of 2.2 percent during 2018. The PCE price index increased 1.4 percent, compared with an increase of 1.9 percent. Excluding food and energy, the PCE price index increased 1.6 percent, compared with an increase of 1.9 percent (table 6).

FULL DOCUMENT: https://www.bea.gov/system/files/2020-02/gdp4q19_2nd.pdf

ECONOMICS

FED. February 25, 2020. Speech. U.S. Economic Outlook and Monetary Policy. Vice Chair Richard H. Clarida. . At the 36th Annual NABE Economic Policy Conference, Washington, D.C.

Thank you for the opportunity to participate again this year in the Annual Economic Policy Conference of the National Association for Business Economics. I am really looking forward to this conversation. But first, I would like to share with you some thoughts about the outlook for the U.S. economy and monetary policy.1

In its 11th year of a record expansion, the U.S. economy is in a good place. The labor market remains strong, economic activity is increasing at a moderate pace, and the Federal Open Market Committee's (FOMC) baseline outlook is for a continuation of this performance in 2020.2 At present, personal consumption expenditures, or PCE, price inflation is running somewhat below the Committee's 2 percent objective, but we project that, under appropriate monetary policy, inflation will rise gradually to our symmetric 2 percent objective. Although the unemployment rate is around a 50-year low, wages are rising broadly in line with productivity growth and underlying inflation. We are not seeing any evidence to date that a strong labor market is putting excessive cost-push pressure on price inflation.

Although the fundamentals supporting household consumption remain solid, over 2019, sluggish growth abroad and global developments weighed on investment, exports, and manufacturing in the United States. Coming into this year, indications suggested that headwinds to global growth had begun to abate, and uncertainties around trade policy had diminished. However, risks to the outlook remain. In particular, we are closely monitoring the emergence of the coronavirus, which is likely to have a noticeable impact on Chinese growth, at least in the first quarter of this year. The disruption there could spill over to the rest of the global economy. But it is still too soon to even speculate about either the size or the persistence of these effects, or whether they will lead to a material change in the outlook. In addition, U.S. inflation remains muted. And inflation expectations—those measured by surveys, market prices, and econometric models—reside at the low end of a range I consider consistent with our price-stability mandate.

Over the course of 2019, the FOMC undertook a shift in the stance of monetary policy to offset some significant global growth headwinds and global disinflationary pressures. I believe this shift was well timed and has been providing support to the economy and helping to keep the U.S. outlook on track. Monetary policy is in a good place and should continue to support sustained growth, a strong labor market, and inflation returning to our symmetric 2 percent objective. As long as incoming information about the economy remains broadly consistent with this outlook, the current stance of monetary policy likely will remain appropriate.

That said, monetary policy is not on a preset course. The Committee will proceed on a meeting-by-meeting basis and will be monitoring the effects of our recent policy actions along with other information bearing on the outlook as we assess the appropriate path of the target range for the federal funds rate. Of course, if developments emerge that, in the future, trigger a material reassessment of our outlook, we will respond accordingly.

In January 2019, my FOMC colleagues and I affirmed that we aim to operate with an ample level of bank reserves in the U.S. financial system.3 And in October, we announced and began to implement a program to address pressures in repurchase agreement (repo) markets that became evident in September.4 To that end, we have been purchasing Treasury bills and conducting both overnight and term repurchase operations. These efforts have been successful in achieving stable money market conditions, including over the year-end. As our bill purchases continue to build reserves toward levels that we associate with ample conditions, we intend to gradually transition away from the active use of repo operations. And as reserves reach durably ample levels, we intend to slow the pace of purchases such that our balance sheet grows in line with trend demand for our liabilities. Let me emphasize that we stand ready to adjust the details of this program as appropriate and in line with our goal, which is to keep the federal funds rate in the target range desired by the FOMC, and that these operations are technical measures not intended to change the stance of monetary policy.

Finally, allow me to offer a few words about the FOMC's review of the monetary policy strategy, tools, and communication practices that we commenced in 2019. This review—with public engagement unprecedented in scope for us—is the first of its kind for the Federal Reserve. Through 14 Fed Listens events, including a research conference in Chicago, we have been hearing a range of perspectives not only from academic experts, but also from representatives of consumer, labor, community, business, and other groups. We are drawing on these insights as we assess how best to achieve and maintain maximum employment and price stability. In July, we began discussing topics associated with the review at regularly scheduled FOMC meetings. We will continue reporting on our discussions in the minutes of FOMC meetings and will share our conclusions with the public when we complete the review later this year.5

Thank you very much for your time and attention. I look forward to the conversation and the question-and-answer session to follow.

Notes

- These remarks represent my own views, which do not necessarily represent those of the Federal Reserve Board or the Federal Open Market Committee. I am grateful to Brian Doyle of the Federal Reserve Board staff for his assistance in preparing this text.

- The most recent Summary of Economic Projections is an addendum to the minutes of the December 2019 FOMC meeting. See Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2020), "Minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee, December 10–11, 2019," press release, January 3.

- See the Statement Regarding Monetary Policy Implementation and Balance Sheet Normalization, which is available on the Board's website at https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/monetary20190130c.htm. Also see the Balance Sheet Normalization Principles and Plans, available on the Board's website at https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/monetary20190320c.htm.

- See the Statement Regarding Monetary Policy Implementation, which can be found on the Board's website at https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/monetary20191011a.htm.

- Information about the review and the events associated with it is available on the Board's website at https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/review-of-monetary-policy-strategy-tools-and-communications.htm.

BOLIVIA

U.S. Department of State. 02/25/2020. Senior State Department Official on U.S. Engagement with Bolivia. Washington, D.C. Press Correspondents’ Room

MODERATOR: All right. Think we’re close enough to quorum, so you guys have already had one of these before. So now we have – joining us from our Western Hemisphere portfolio, . This will be on background, attribution to a senior State Department official. He has some remarks up front and then he’ll take some of your questions, okay?

Go ahead.

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: Hello, everybody, and hope you’re having a nice afternoon on this rainy Washington Tuesday. I would like to talk a bit about Bolivia, and I do have some opening remarks, and afterwards, of course, we’ll proceed to questions.

Let me first say that this is a really momentous time in Bolivia’s history. Bolivia is at an inflection point. It’s – there’s an election coming up. On May 3rd, the Bolivians go to the polls in what amounts to probably the most important election in the country’s history. After the fraud that marred the October 20th balloting, this is the most important election to the country’s history. It has to go right.

And what’s at stake is this: This is a chance for Bolivians to put in place a diverse, inclusive, just, fair country, prosperous as well, that respects the rule of law. That’s what Bolivians want and that’s a chance to actually do this. That’s why it’s just so important.

After the fraud-marred elections on October 20th, the Bolivian people stood up and demanded that their vote be respected. They were justifiable in objecting to the deterioration of Bolivia’s democratic institutions under the previous government. President Morales – ex-President Morales resigned on November 10th and he left the country to go to Mexico after a dozen of his own supporters, ministers, deputies, senators, et cetera resigned. He also lost support of the largest labor organization in the country and that was in many ways the motivating factor behind his departure. After that, Bolivia remained under civilian control at all times and a succession took place in line with the constitutional provisions.

There is a transitional government in place. It’s headed by Transitional President Jeanine Anez. They have worked out a calendar – electoral calendar in conjunction with the legislative assembly, the Bolivians’ congress. That congress actually is controlled, both chambers, by the MAS party – the former government party but now the opposition party. So what happened was the country’s new leaders sat down and figured out a way forward. New elections will take place, first round, on May 3rd. If a second round is necessary – and I can get into the provisions as to why there would be a second round or not – that would be on June 14th and the inauguration would be on July 22nd, possibly delayed till August 6th depending upon who won.

What is the U.S. Government doing? Well, we’re working with the international community – our partners in the EU, the UN, the OAS – to help ensure free, fair, and transparent elections that would help bolster democracy. All Bolivians need to come together to support the upcoming elections and refrain from violence to make sure that they go well. I very much hope that that will happen.

The United States wants a positive relationship with the new government of Bolivia, whatever government that is put in place. Under Secretary David Hale visited La Paz in January, and on January 21st announced our intent to return ambassador – to an ambassador relationship – relationship at the ambassador level with Bolivia. This is after 14 years of antagonism under the Morales government, so whatever government that is put in place, we do hope to exchange ambassadors. I think that would be bilateral as well.

We’re talking with the Bolivian government – the transitional government right now on medium and long-term initiatives that could be put in place after a new government is sworn in. In addition, there’s some short-term measures we hope to take that would benefit Bolivia as well.

Again, just to summarize, this is an important time for Bolivia. It needs the support of the international community. And the United States with our partners – the EU, the UN, other Western countries – that’s what we’re working to do. Thank you.

MODERATOR: Questions.

QUESTION: Yeah. So recognizing that we’re still, what, two months away? Two months or a month?

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: I think it’s 68 days or so.

QUESTION: Okay. Well —

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: That may be —

QUESTION: But who’s counting?

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: Give a day or two. Every day is a miracle.

QUESTION: You’re not really paying close attention, are you? (Laughter.) I mean, how do things look? Recognizing that we’re still two months away, what – does it look like the ground has been prepared for an election that will meet the free, fair, and credible standard?

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: The body that’s actually responsible for organizing, holding, and conducting elections is the Tribunal Superior Electoral. In English, the acronym is TSE. The president of the TSE was chosen by Anez and the members were chosen by the Bolivian congress. Again, a MAS – Morales party – MAS-dominated congress. They worked well together, but to organize an election in a short span of time like 120 days is difficult. But they’ve had an immense amount of technical assistance from the UN. We’re chipping in as well through partners. The EU is there as well.

But the problem is this: In order to run the election – I’m sorry I’m going on, but you need to do certain things at certain times. So for publicity, public communications, that has to be done. For printing of ballots, that has to be done by X date, and Y date doesn’t really help because it has to be done by X date. Distribution of the ballots, the transportation systems, that’s all logistical.

Now, for the prior election, the TSE, the electoral body had two years to prepare. This one, 120 days. The system was – you can rely upon the old system, but that’s the challenge right now.

QUESTION: But is that the big – that’s the biggest red flag right now, is that they might not be logistically capable of —

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: Or as the president at the TSE says, one way or the other they’ll be ready, but it’s a challenge.

MODERATOR: Okay, (inaudible).

QUESTION: But haven’t a lot of the potential candidates either been arrested or disqualified, up to 30 percent, I believe, which when we – we hear in this building a lot – just last week – when Iran does that, there is a blanket condemnation of those kinds of election preparations, when Venezuela does something similar? So why should we not judge Bolivia by those standards? And are you – is the American Government delivering a certain message to the sitting authorities now in Bolivia that they need to – what is the message to them to make this more fair?

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: There are two parts to this answer. One is that there are certain requisites to be a candidate, and several parties – not necessarily the major parties – submitted a slate of congressional, senate candidates – and I’ll talk about presidential later – where they didn’t fulfill the requisites. I mean, you need to have X, Y, Z there, and they may have had X or X and Y. So under the rule of law, if they don’t have X, Y, and Z and the law requires X, Y, and Z, then they need to be disqualified. But that was more for several minor parties.

I think the larger issue is the presidential race, and – actually the presidential race and then Morales, who submitted a candidacy for the senatorship of Cochabamba, and ex-Foreign Minister Pary, who submitted a candidateship for senatorship – candidacy for the senate of Potosi, two different departments. So objections were lodged against both Morales and Pary – P-a-r-y – for the candidacy because they didn’t live in the district, and the Bolivian constitution specifies that you need to have lived in your district for two years. In the case of president, you need to have lived in the country for two years; in the case of senator, you would need to have lived in that senator department for two years.

So four main candidates were challenged. One was an opposition candidate who was living in the United States, so she was disqualified. Another was another opposition candidate who was, again, either living in the United States or out of the country. He was easily disqualified. When I say “opposition,” I mean former opposition, government-aligned. So there would be MAS and then there’d be opposition, but —

QUESTION: But these were MAS candidates or these were —

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: The two that were —

QUESTION: That were disqualified were MAS?

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: No. The two were what we call the former opposition, but we don’t have a name for it, so we just call them former opposition. But now they’re aligned with the government.

So the two that were MAS were Morales, who is now living in Argentina and before that was living in Mexico, so he was disqualified; and Pary – former Foreign Minister Pary – he was disqualified because he lived in the United States for seven years, came back and lived in Bolivia for one year, and then voted in La Paz but his district would have been Cochabamba. So all this seems to have been in line with – reasonable decisions in line with the governing electoral law.

QUESTION: So you’re saying the disqualifications are reasonable and should not raise suspicions in a public that’s going to be suspicious about it?

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: I could have said that all a little bit quicker if I just simply said – yes.

QUESTION: Sorry. We’re journalists, and you’re a diplomat.

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: They were based upon reasons, yes.

MODERATOR: Who’s next? Jenny.

QUESTION: Do you think Morales has any chance of coming back? Is he still popular at all? Does he still have some sort of base of support, or are people moving on?

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: Well, I think there’s two aspects to that question. Does – first is does Morales have a chance to come back. The other is does the MAS have a chance to come back. The MAS – I’ll do the second first. The MAS has a candidate, Luis Arce, for president, and for vice president, David Choquehuanca. Arce is the former economy minister for MAS. Choquehuanca is the former foreign minister – another former foreign minister for MAS.

In the most recent polling, they had – in order to win the presidency, you need to have – in the first round, you need to have a 40 percent vote – valid vote – 40 percent of the valid vote and a 10 percent margin over the nearest competitor. So 40 to 29 wins it for you; 40 to 31 doesn’t. In the most recent two polls, it became clear that Arce and Choquehuanca, the two MAS candidates, have a good chance of perhaps reaching 40 percent. The – but the question is would they have a 10 percent margin over their nearest competitor. So yes, the MAS does have a chance. It – I don’t want to qualify whether it’s a good chance or a significant chance, but yeah, they have a chance in a free and fair election.

Now for Morales, he’s disqualified from that election for electoral fraud on October 20th. So he cannot come back for another five years. At this point, I don’t – can’t speculate as to whether he remains in Argentina or not, but the MAS has a chance. Morales is out of the country, and at this point only he knows his future plans.

QUESTION: Jessica.

QUESTION: What’s your assessment of how the interim government has been forming? Are they a disappointment?

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: I’m sorry. I didn’t hear that first one.

QUESTION: What is your assessment of how the interim government has been forming? Do you – would you consider the fact that they’ve gone back on some of their promises, like not to run for office, not to make major changes – is that a disappointment?

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: I wouldn’t use that characterization. On November 10th, former President Morales resigned, and through a – the vice president resigned as well. The – going through the list of constitutional succession, the president of the senate resigned. The second – first vice president of the senate resigned, and the head of the lower house resigned. That left in the constitutional succession the second vice president of the senate, which was Jeanine Anez, the current head of the transitional government.

So before November 10th, she had no idea she might even be president. She was sworn in November 12th. There were some security incidents. I think she had to go into hiding. The cabinet was sworn in I think on the 12th or the 14th. Many of them hadn’t even met each other before. But what they were able to do is come to an agreement with the new MAS leaders of the senate and the chamber of deputies, come to an agreement on an electoral calendar to help pacify the country, settle people down. That was a really brilliant, big achievement. They set an election date. They agreed upon an electoral body. For a government that’s a transitional government, that was their main function and they’ve done it.

Now, the country still needs to be governed in the meantime until the May elections, and there’s been a debate back and forth as to the bounds of what the transitional government should do. But the fact that they’ve done job one of setting an electoral calendar and putting that in place I think is an incredible achievement. And it was done peacefully.

Ma’am.

MODERATOR: Yes, Kim.

QUESTION: Hi. Kim Dozier from TIME. I apologize if you addressed this in your remarks. But I’m wondering from your position how is Latin America positioned for a coronavirus outbreak?

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: I can’t talk about Latin America, but I can talk about Bolivia. Bolivia has not had any coronavirus cases. What it has had, unfortunately, is a severe outbreak of Dengue fever. And Bolivia’s geography is such that in the highlands of La Paz, you don’t have mosquitos because they can’t survive at that altitude. But in the eastern lowlands of Santa Cruz, a city of two million people, it’s tropical and there is a violent, virulent Dengue outbreak, and a number of people have died. I think it’s in the 20s and 30s, but it may be underestimated because some cases of Dengue are asymptomatic.

So, so far, even though there’s substantial international travel back and forth between Asia, or for that matter to the United States and the rest of South America, the coronavirus has not appeared. So when people talk about corona, we go back and talk about Dengue, which is a danger.

QUESTION: But I’m just wondering how – if the health system is hit with a sweeping pandemic of some sort, are they – do they have the resources to combat it?

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: I think it would be difficult for any country to combat it, including ours. But I’m not a health professional.

QUESTION: What do you think about —

MODERATOR: Excuse me, who are you?

QUESTION: (Inaudible) from foreign press – AFP.

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: Okay.

QUESTION: I’d like to know how you see Jeanine Anez as a future – as a candidate. What does the United States think about her running for president?

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: She’s done a good job as a transitional president, and I think, based upon – again, we have an election date. There’s peace in the country and the country’s moving forward. Now, I’m not going to evaluate different candidates simply because I’m an American, and that’s something for Bolivians to do. But —

QUESTION: She said that she wasn’t running. That’s why – she changed afterwards.

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: She initially said that she was not going to run. She has subsequently decided to run. That’s her decision. But again, we don’t support or oppose any candidate. It’s – the importance of democracy is that those governed decide. And so I’m not going to opine as to her merits versus some other candidate. We’ll work with other – whatever Bolivian government that is elected on May 3rd or June 14th and sworn in later.

MODERATOR: Okay. Humeyra.

QUESTION: Hi, and I’m sorry if you mentioned this before, but I just wanted to ask you about Chinese interest in the lithium industry. They had signed a deal, but that was last year, and we’ve had an – I’m from Reuters – we’ve had an interview with the state-owned company, and they said they’re looking at various options, various partnerships. Is this – and that the Chinese partnership was being reassessed. Is this a point of concern for U.S.? And if it is, what are you doing to counter that Chinese influence there? Thank you.

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: The Chinese deal is one deal that was signed under the previous Morales government. Yet another was done – signed with the Germans.

QUESTION: Germany.

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: The Morales government signed a deal with the Germans then renounced it prior to the election in the wake of protests in the department of Potosi. The Chinese deal, I think, is simply – has to do with one region in the vast Salar de Uyuni, the Uyuni Salt Flats. But in many ways, at least in my point of view, what’s more important is the German deal, which is still up in the air, unclear. Because the Germans would provide the technology to take Bolivia’s lithium pods, which have a fair amount of moisture content, take out the moisture content and make them more easily refined, similar to the lower moisture contents of the lithium deposits of Argentina and Chile. Bolivia has mass lithium reserves. It just – the moisture makes it a technological challenge. That’s why the German deal, in many ways, is more important than the Chinese deal.

QUESTION: So in a way, the German deal is something you guys actually support or encourage or would like to happen? Is that what you mean?

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: We would support the idea of Bolivia having the technology to exploit its lithium reserves.

QUESTION: Yeah. And them doing a deal with China, would that like worry you? Or —

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: I don’t believe China actually has – I think it’s an apple and an orange, because the Chinese technology is – the Chinese deal is not based upon a technology transfer.

QUESTION: Right, it’s just extraction.

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: Yes.

QUESTION: And so that —

QUESTION: Oh, okay, that’s why – the German one is better for the U.S., I guess, the German deal’s better. It makes – it’s aligned with what you were saying before about —

SENIOR STATE DEPARTNET OFFICIAL: I believe that like a deal with a U.S. firm is always better for the U.S., but Bolivia in the end needs technology.

MODERATOR: Okay, one or two more.

QUESTION: I just have a question about the meetings here in Washington, what the mood is in this – as a lot of people come back, I mean, there’s a lot of acting positions right now at the State Department, including in your bureau. Is that having any effect on your work? The administration keeps cutting the budget for foreign affairs by large amounts each year. Is that having an impact?

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: Let me put it this way: I’m just speaking for WHA bureau, and I’ve worked in the department for 35 years, but the people I work with in WHA who deal with Bolivia I’ve known for either two or three decades – maybe two. So – and I’ve worked with them before. And so we work well together, and it’s based upon a back and forth of trust. There’s no micromanagement. At the same time, we report back. So from my point of view, things are working well.

MODERATOR: Great. One more. Yeah.

QUESTION: From what I understand, Morales maintains a level of influence, even from his position in Argentina, in the MAS candidates. Are you concerned at all that the candidates would not be acting on their own but really at his behest?

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: I’m glad you touched upon that. What we’re seeing within the MAS is actually a division. And there are various names as to the two sides, but one camp is the Morales-dominated Argentina camp, where he has some of his former ministers there, and they make decisions about what will happen in faraway Bolivia from Buenos Aires. The other camp is composed of former MAS parliamentarians, many of whom – or when they were in congress, never even got a chance to speak to Evo. They simply had to take orders as to what he did. That was the party structure.

They’re embarking upon an independent moving saying decisions should be made in Bolivia and by Bolivians. And that is a quite interesting, I think, development. And so we’re seeing a range of viewpoints within the MAS as to how the party should move forward, and that benefits democracy. It benefits democracy within the MAS; it benefits democracy within Bolivia.

MODERATOR: Thank you.

QUESTION: Thank you.

Tribunal Supremo Electoral

CHINA

U.S. Department of State. 02/27/2020. PRC Sentencing of Gui Minhai. Morgan Ortagus, Department Spokesperson

We strongly condemn the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) sentencing of Swedish citizen Gui Minhai on February 24. We call on the PRC government to release him immediately and unconditionally. The United States and our partners are bound by shared principles of rule of law, liberty, equality, and human dignity. We will continue to stand with our partners and allies to promote greater respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms in China.

U.S. Department of State. 02/27/2020. Secretary Pompeo’s Meeting with Finnish Foreign Minister Haavisto

The below is attributable to Spokesperson Morgan Ortagus:

Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo met today with Finnish Foreign Minister Pekka Haavisto in Washington, D.C. Secretary Pompeo and Foreign Minister Haavisto exchanged views on transatlantic security and the importance of countering Russian and Chinese malign activity. They also discussed prospects for continued security and defense cooperation between the United States and Finland.

________________

ORGANISMS

MILLENNIALS

IMF. FEBRUARY 27, 2020. The Declining Fortunes of the Young

By Era Dabla-Norris , Carlo Pizzinelli, and Jay Rappaport

Will I do as well as my parents?

A positive answer to this question once seemed a foregone conclusion; now, for recent generations, less so. Despite being more educated than their parents, millennials—those born between 1980 and 2000—may have less job stability during their working life. Concerns that it might be more difficult to break into the middle class, or to have enough retirement savings, are also rising to the fore in policy debates in many advanced economies.

These concerns stem from the fact that the nature of work and the economic returns to different skills and education-levels are changing rapidly. The number of well-paid middle-skill jobs in manufacturing and clerical occupations has decreased substantially since the mid-1980s in the United States and Europe. Job opportunities today are more concentrated in relatively high-skill, high-wage jobs and low-skill, low-wage jobs.

Despite being more educated than their parents, millennials may have less job stability during their working life.

This “hollowing out” of the middle classes has been linked to the disappearance of routine occupations—jobs with a higher share of tasks performable through a set of easily codified rules (such as bookkeeping, clerical work, and some manufacturing jobs)— driven by technological progress and global integration.

Automation and artificial intelligence continue to replace workers and may also limit job creation in growing sectors. By extension, younger workers’ wages may stagnate, or they may be forced to move to low-skill and low-pay occupations.

At the same time, earnings and income gaps between generations have widened significantly in many countries. Many of these trends were exacerbated by the global financial crisis. In Europe, for instance, incomes declined for young people after the 2007 crisis due to unemployment. They have since recovered but have not grown. The rise of the so-called “gig” economy, and increases in temporary contracts, exacerbated the problem and further decreased job stability, particularly for the young.

New IMF staff research has zoomed-in on how these trends vary by gender and the level of education using labor force data from the United Kingdom over the period 2001–2018.

Non-college educated workers

In the United Kingdom, workers without a college (university) degree have experienced the most drastic decline in routine jobs. Non-college-educated workers are 5 to 15 percentage points less likely to be employed in routine jobs now than they were two decades ago. This trend has had a big impact on younger generations, as middle-wage, middle-skill job opportunities they would take up continue to evaporate.

But labor market opportunities for non-college educated young women appear most affected. They are increasingly likely to be employed in low-skill manual-based jobs, and their real wages over all occupations have fallen in the past two decades. Millennial women’s wages today are more than 10 percent lower than those of women in the baby boomer generation, almost double the gap that exists for their male counterparts.

College-educated workers

College (university) educated workers in the United Kingdom face different challenges. The share of college-educated workers increased from 29 percent in 2001 to 45 percent in 2018. As attainment of higher education rises for younger generations, the returns to a university degree are falling. IMF staff research find that, although an undergraduate degree still leads to a much higher likelihood of having a “good job,” it presents less of a guarantee than it did in the past in the United Kingdom. Other research suggests this is the case for the United States as well. The two criteria of a “good job” are wages and the extent of abstract-thinking in a job’s tasks, which can be complementary to technology. An abstract job is one that typically requires creative, problem-solving, and coordination tasks performed by professionals and managers.

The share of abstract jobs among the highly-educated has fallen between 2001 and 2018. In recent years, both highly-educated male and female workers have become more likely to take middle-skill jobs compared to less-educated workers. Therefore, for members of recent generations, a college education does less to ensure a high-paying job in an abstract job than it did for their parents. The widening gap between the wages of the young and those of older people since the Global Financial Crisis, although narrowing more recently, is also of concern.

Policy Solutions

Policy responses to automation should focus on building skills to complement automation and reducing the impact of job displacement to workers both in the short and long run.

In the short term, policies should create new opportunities for people displaced by automation, particularly for low-skilled workers. Additionally, supporting research and development fields can help employ college-educated workers in areas such as science and technology. Removing legal barriers to employment and allowing for more flexible contracts may also help more young people get jobs.

Over the long term, education and skills training programs need to prepare participants to meet the adjusted demands of the labor market. College graduates should be literate in, and easily capable of using, technology for their chosen sector.

FULL DOCUMENT: https://blogs.imf.org/2020/02/27/the-declining-fortunes-of-the-young/?utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery

________________

ECONOMIA BRASILEIRA / BRAZIL ECONOMICS

INFLAÇÃO

FGV. IBRE. 27/02/20. Índices Gerais de Preços. IGP-M. IGP-M varia -0,04% em fevereiro

O Índice Geral de Preços – Mercado (IGP-M) variou -0,04% em fevereiro, percentual inferior ao apurado em janeiro, quando a taxa foi de 0,48%. Com este resultado, o índice acumula alta de 0,44% no ano e de 6,82% em 12 meses. Em fevereiro de 2019, o índice havia sido de 0,88% e acumulava alta de 7,60% em 12 meses.

O Índice de Preços ao Produtor Amplo (IPA) caiu 0,19% em fevereiro, após alta de 0,50% em janeiro. Na análise por estágios de processamento, a taxa do grupo Bens Finais variou -0,55% em fevereiro, contra 0,02% no mês anterior. A principal contribuição para este resultado partiu do subgrupo alimentos processados, cuja taxa passou de -0,44% para -1,57%, no mesmo período. O índice relativo a Bens Finais (ex), que exclui os subgrupos alimentos in natura e combustíveis para o consumo, variou -0,40% em fevereiro, ante 0,01% no mês anterior.

A taxa de variação do grupo Bens Intermediários variou de 1,21% em janeiro para -0,33% em fevereiro. O principal responsável por este movimento foi o subgrupo combustíveis e lubrificantes para a produção, cujo percentual passou de 4,20% para -3,67%. O índice de Bens Intermediários (ex), obtido após a exclusão do subgrupo combustíveis e lubrificantes para a produção, subiu 0,30% em fevereiro, contra 0,66% em janeiro.

O índice do grupo Matérias-Primas Brutas passou de 0,26% em janeiro para 0,36% em fevereiro. Contribuíram para o avanço da taxa do grupo os seguintes itens: bovinos (-5,83% para -1,06%), mandioca (aipim) (-3,43% para 4,93%) e leite in natura (1,01% para 2,77%). Em sentido oposto, destacam-se os itens minério de ferro (1,43% para -0,01%), milho (em grão) (8,26% para 5,17%) e soja (em grão) (-1,78% para -2,97%).

O Índice de Preços ao Consumidor (IPC) variou 0,21% em fevereiro, após alta de 0,52% em janeiro. Seis das oito classes de despesa componentes do índice registraram recuo em suas taxas de variação. A principal contribuição partiu do grupo Alimentação (1,22% para 0,28%). Nesta classe de despesa, vale citar o comportamento do item carnes bovinas, cuja taxa passou de 1,95% para -4,59%.

Também apresentaram decréscimo em suas taxas de variação os grupos Transportes (0,82% para 0,09%), Despesas Diversas (0,29% para 0,14%), Comunicação (0,16% para 0,05%), Habitação (-0,05% para -0,10%) e Saúde e Cuidados Pessoais (0,38% para 0,36%). Nestas classes de despesa, vale mencionar os seguintes itens: gasolina (2,16% para -0,88%), serviços bancários (0,26% para 0,08%), mensalidade para TV por assinatura (1,09% para 0,13%), tarifa de eletricidade residencial (-1,08% para -1,29%) e salão de beleza (0,43% para 0,20%).

Em contrapartida, os grupos Educação, Leitura e Recreação (0,66% para 1,04%) e Vestuário (-0,04% para 0,06%) apresentaram acréscimo em suas taxas de variação. Nestas classes de despesa, os maiores avanços foram observados para os seguintes itens: passagem aérea (-8,50% para 0,34%) e roupas (-0,23% para 0,07%).

O Índice Nacional de Custo da Construção (INCC) subiu 0,35% em fevereiro, ante 0,26% no mês anterior. Os três grupos componentes do INCC registraram as seguintes variações na passagem de janeiro para fevereiro: Materiais e Equipamentos (0,47% para 0,65%), Serviços (0,37% para 0,96%) e Mão de Obra (0,09% para 0,04%).

DOCUMENTO: https://portalibre.fgv.br/navegacao-superior/noticias/igp-m-varia-0-04-em-fevereiro.htm

FGV. IBRE. 27/02/20. Índices Gerais de Preços. IPC-S. Inflação pelo IPC-S recua na terceira semana de fevereiro

O IPC-S de 22 de fevereiro de 2020 variou 0,17%, ficando 0,19 ponto percentual (p.p) abaixo da taxa registrada na última divulgação.

Nesta apuração, sete das oito classes de despesa componentes do índice registraram decréscimo em suas taxas de variação. A maior contribuição partiu do grupo Educação, Leitura e Recreação (1,63% para 0,69%). Nesta classe de despesa, cabe mencionar o comportamento do item passagem aérea, cuja taxa passou de 4,42% para -0,88%.

Também registraram decréscimo em suas taxas de variação os grupos: Transportes (0,32% para 0,07%), Habitação (-0,02% para -0,15%), Despesas Diversas (0,30% para 0,16%), Alimentação (0,39% para 0,30%), Saúde e Cuidados Pessoais (0,37% para 0,33%) e Comunicação (0,08% para 0,02%). Nestas classes de despesa, vale destacar o comportamento dos itens: gasolina (-0,21% para -1,03%), tarifa de eletricidade residencial (-0,72% para -1,52%), serviços bancários (0,36% para 0,08%), hortaliças e legumes (9,50% para 7,49%), artigos de higiene e cuidado pessoal (0,55% para 0,30%) e mensalidade para tv por assinatura (0,39% para 0,13%).

Em contrapartida, o grupo Vestuário (-0,17% para 0,22%) apresentou avanço em sua taxa de variação. Nesta classe de despesa, vale citar o item roupas (-0,26% para 0,19%).

DOCUMENTO: https://portalibre.fgv.br/navegacao-superior/noticias/inflacao-pelo-ipc-s-recua-na-terceira-semana-de-fevereiro.htm

FGV. IBRE. 27/02/20. Índices Gerais de Preços. IPC-S Capitais. Inflação pelo IPC-S recua em todas as sete capitais pesquisadas

O IPC-S de 22 de fevereiro de 2020 registrou variação de 0,17%, ficando 0,19 ponto percentual (p.p.) abaixo da taxa divulgada na última apuração. Todas as sete capitais pesquisadas registraram decréscimo em suas taxas de variação.

A tabela a seguir, apresenta as variações percentuais dos municípios das sete capitais componentes do índice, nesta e nas apurações anteriores.

DOCUMENTO: https://portalibre.fgv.br/navegacao-superior/noticias/inflacao-pelo-ipc-s-recua-em-todas-as-sete-capitais-pesquisadas-3.htm

POLÍTICA MONETÁRIA

BACEN. 27 Fevereiro 2020. BC divulga Estatísticas Monetárias e de Crédito à imprensa

com os dados atualizados até janeiro de 2020.

1. Crédito ampliado ao setor não financeiro

Em janeiro, o crédito ampliado ao setor não financeiro alcançou R$10,3 trilhões (141,5% do PIB), variação de 0,4% no mês. O saldo de empréstimos e financiamentos e de títulos de dívida caíram 0,4% e 1%, respectivamente, enquanto a dívida externa cresceu 5,1%, impulsionada pela depreciação cambial. Na comparação interanual, o crédito ampliado cresceu 12%, resultado das expansões de 7,1% nos empréstimos e financiamentos, de 14,8% em títulos de dívida e de 15,2% na dívida externa.

O crédito ampliado a empresas e famílias somou R$5,8 trilhões (79,3% do PIB), com aumentos de 0,9% no mês e de 12,4% em doze meses. No mês, o crescimento foi influenciado pela variação cambial da dívida externa, cujo estoque aumentou 5,2%, enquanto o saldo de empréstimos e financiamentos e das captações no mercado de capitais (títulos e instrumentos securitizados) diminuíram 0,4% e 0,8%, na ordem. Em doze meses, destaque-se a ampliação de 30,5% no saldo do mercado de capitais.

2. Operações de crédito do Sistema Financeiro Nacional (SFN)

O saldo das operações de crédito do sistema financeiro nacional (SFN) totalizou R$3,5 trilhões em janeiro, queda de 0,4% no mês, com redução de 2,2% na carteira de pessoas jurídicas (saldo de R$1,4 trilhão), influenciada pela sazonalidade, e aumento de 0,8% em pessoas físicas (R$2 trilhões). O crescimento em doze meses do estoque de crédito do SFN alcançou 7%, resultado das expansões de 12,2% no crédito às famílias e de 0,4% no crédito às empresas.

O crédito livre a pessoas físicas somou R$1,1 trilhão, acréscimos de 1,1% no mês e de 16,6% em doze meses, com destaque para crédito pessoal (consignado e não consignado), veículos e cheque especial. O crédito livre para pessoas jurídicas alcançou R$872 bilhões, com redução de 3,1% no mês e elevação de 11,4% em doze meses, refletindo as liquidações sazonais das modalidades relacionadas a fluxos de caixa, como desconto de duplicatas e recebíveis e antecipação de faturas de cartão.

No crédito direcionado, as operações com pessoas físicas atingiram R$909 bilhões, crescendo 0,5% e 7,1%, respectivamente, no mês e em doze meses, com aumentos nas modalidades rural e imobiliário. A carteira de pessoas jurídicas recuou 0,7% e 13% nos mesmos períodos, situando-se em R$556 bilhões em janeiro.

As concessões totais de crédito do SFN somaram R$322 bilhões em janeiro, declínio de 19% no mês, influenciada por fatores sazonais. A estatística de concessões de crédito ajustada sazonalmente apresentou redução de 0,3%, com quedas de 0,1% em pessoas físicas e jurídicas. Na comparação com janeiro de 2019, as concessões cresceram 13,6% (15,5% no crédito às famílias e 10,8% com empresas).

O Indicador de Custo do Crédito (ICC), que mede o custo médio de toda a carteira do sistema financeiro nacional, situou-se em 20,2% a.a., com reduções de 0,1 p.p. no mês e de 0,5 p.p. na comparação interanual. No crédito livre não rotativo, o ICC alcançou 27,1%, aumentando 0,2 p.p. em relação a dezembro e diminuindo 2,1 p.p. na comparação com janeiro de 2019. O spread geral do ICC situou-se em 14,4 p.p., registrando estabilidade no mês e aumento de 0,5 p.p. em doze meses.

A taxa média de juros das operações contratadas em janeiro alcançou 23% a.a., elevação de 0,4 p.p. no mês e declínio de 1,4 p.p. em doze meses. O spread geral das taxas das concessões situou-se em 18,3 p.p., o que representou variações de 0,5 p.p. e de 0,1 p.p., nas mesmas bases de comparação.

No crédito livre, a taxa média de juros das concessões atingiu 33,7% a.a., variando 0,3 p.p. no mês e -3,4 p.p. na comparação interanual. No segmento das famílias, a taxa média situou-se em 45,6% a.a. (-0,4 p.p. e -4,5 p.p., respectivamente), destacando-se a redução na taxa de juros do cheque especial, que alcançou 165,6% a.a. em janeiro (8,5% a.m.), com quedas de 82 p.p. no mês e de 101,7 p.p. em doze meses. Essa redução refletiu a entrada em vigor da Resolução nº 4.765, de 27.11.2019, que limitou em 8% a.m. as taxas de juros remuneratórios cobradas sobre o valor utilizado do cheque especial de pessoas físicas e microempreendedores individuais. A estatística de taxa média de juros das concessões inclui – além dos juros remuneratórios, que são o objeto da Resolução nº 4.765/2019 – os encargos fiscais e operacionais incidentes sobre a operação de crédito, bem como os descontos decorrentes de benefício de prazo com isenção ou redução de juros na utilização do cheque especial (conforme tratado no item 4.1 abaixo). Além disso, são incorporadas operações de adiantamentos a depositantes, cujo saldo não é significativo na comparação com o do cheque especial.

No crédito livre às empresas, a taxa média das concessões alcançou 17,6% a.a. em janeiro, aumento de 1,3 p.p. mês e redução de 2,8% em doze meses. A elevação mensal ocorreu em diversas modalidades (desconto de duplicatas e recebíveis: 2,4 p.p.; capital de giro: 1,8 p.p., entre outras), refletindo variação sazonal no custo das contratações.

3. Agregados monetários

A base monetária totalizou R$318 bilhões em janeiro, crescimento de 0,4% no mês e de 13,9% em doze meses. No mês, as reservas bancárias cresceram 68,6% e o papel-moeda emitido recuou 8,3%. Entre os fluxos mensais dos fatores condicionantes da base monetária, foram contracionistas as operações com títulos federais, em R$5,2 bilhões (resgates líquidos de R$55,6 bilhões no mercado primário e vendas líquidas de R$60,8 bilhões no mercado secundário), as operações do Tesouro Nacional (R$1,4 bilhões) e os depósitos de instituições financeiras (IFs), R$555 milhões. De forma expansionista, as operações com derivativos alcançaram R$7,6 bilhões e as operações do setor externo, R$424 milhões, resultante das operações de recompra a termo.

Os meios de pagamento restritos (M1) alcançaram R$398 bilhões, queda de 9,8% no mês, com reduções de 12,5% nos depósitos à vista e de 7,3% no saldo do papel-moeda em poder do público. Considerando-se dados dessazonalizados, o M1 cresceu 6,6% em janeiro.

O M2 totalizou R$3,0 trilhões, recuo de 2,2% no mês. Além da redução no M1, ocorreram contrações de 0,8% no saldo dos títulos emitidos por IFs (R$1,8 trilhão) e de 1,2% nos depósitos de poupança (R$839 bilhões). No mês, foram registrados resgates de R$19,3 bilhões nos depósitos a prazo e de R$12,4 bilhões nos depósitos de poupança. O M3 recuou 0,8% no mês, atingindo R$6,7 trilhões e acompanhando a retração nos agregados mais restritos, que contrabalançou o aumento de 0,8% no saldo das quotas de fundos do mercado monetário (R$3,5 trilhões). O M4 registrou queda de 0,9% no mês e elevação de 7,2% nos últimos 12 meses, encerrando o mês em R$7,2 trilhões.

4. Revisões nas estatísticas de crédito

De acordo com a Política de Revisão das Estatísticas Econômicas Oficiais Compiladas pelo Departamento de Estatísticas (DSTAT) do Banco Central do Brasil (BCB), de outubro de 2019, as estatísticas de crédito sofrem revisão ordinária anual nos meses de fevereiro. As revisões nas estatísticas de crédito, divulgadas nesta Nota para a Imprensa, refletem aprimoramentos metodológicos e de fontes de dados, correção de informações prestadas pelos fornecedores de dados, inclusão de estimativas, maior consistência com outras séries estatísticas, ampliação da cobertura e reclassificações setoriais.

O texto da Nota para a Imprensa – Estatísticas Monetárias e de Crédito, divulgado em janeiro, enumerou os principais itens que compõem esta revisão, detalhados a seguir.

4.1. Taxa de juros do cheque especial

As taxas médias de juros das concessões do cheque especial, pessoas físicas e jurídicas, foram revisadas, a partir de março de 2011, para refletir os aprimoramentos metodológicos introduzidos pela Carta-Circular nº 3.932, de 20.2.2019, referentes ao período de utilização dessa modalidade de empréstimo sem a incidência de juros ou com a cobrança de juros reduzidos. Esse aprimoramento metodológico é consistente com o conceito de Custo Efetivo Total (CET) de uma operação de crédito, que deve considerar, além dos juros, os demais encargos fiscais e operacionais incidentes sobre a operação, bem como os descontos concedidos.

A Carta-Circular nº 3.932/2019 instituiu, a partir de setembro de 2019, para as IFs que concedem o benefício de prazo com isenção ou redução de juros para seus clientes na utilização da linha de crédito de cheque especial, a prestação de informação ao BCB da "taxa média de juros ajustada" dessa modalidade. Para o período anterior a setembro de 2019 a série foi revisada com base nas informações reportadas pelas principais IFs que operam nessa modalidade.

Devido à necessidade de apuração, por parte das IFs, da parcela de clientes que efetivamente pagou juros e da parcela isenta, essa informação é encaminhada ao BCB até o dia 5 do segundo mês subsequente ao de referência. Portanto, a taxa média de juros do cheque especial, na primeira publicação, será estimada, sendo substituída pela informação encaminhada pelas IFs no mês seguinte.

Como resultado da revisão, a taxa média de juros das concessões do cheque especial a pessoas físicas, em dezembro de 2019, passou de 302,5% a.a. (estatística divulgada em janeiro) para 247,6% (estatística revisada). Nas concessões a pessoas jurídicas a taxa reduziu-se de 331,5% a.a. (estatística divulgada em janeiro) para 310,9% (estatística revisada).

4.2. Concessões de crédito com recursos livres

I) Concessões de crédito consignado

As concessões de crédito consignado para servidores públicos e beneficiários do INSS foram revisadas, a partir de janeiro de 2017, para correção de informações prestadas por algumas IFs, referentes a renegociações e portabilidade, indevidamente incluídas nas concessões. A inclusão de renegociações e portabilidade superestimava as concessões de crédito consignado, cuja evolução se mostrava inconsistente com a dos saldos.

Carta-Circular nº 4.000, de 28.1.2020, reforçou orientação constante do Documento 3050 - Estatísticas Agregadas de Crédito e Arrendamento Mercantil - Instruções de Preenchimento" para que renegociações e portabilidade não sejam informadas como novas concessões e determinou que seja incluído nas informações das concessões o valor adicional concedido ao cliente quando da renegociação, denominado "troco".

As informações, com metodologia revisada, serão reportadas ao BCB a partir de 3 de julho deste ano. A série foi revisada a partir de 2017, com base em informações recebidas de IFs e de estimativas. Nessas estimativas, considerou-se as concessões mensais como componente da variação dos saldos mensais, após a exclusão de montante relativo à inadimplência e do cálculo dos pagamentos de principal e juros pelo método Price. As variáveis utilizadas na estimativa das concessões de crédito consignado para servidores públicos e beneficiários do INSS foram: saldo, taxa de inadimplência, ICC e prazos médios das carteiras.

Como resultado da revisão, as concessões de crédito consignado total, em dezembro de 2019, passaram de R$24,6 bilhões (estatística divulgada em janeiro) para R$19,1 bilhões (estatística revisada) e a taxa de variação do acumulado em doze meses, de 41,4% (estatística divulgada em janeiro) para 25,1% (estatística revisada).

II) Concessões de cartão de crédito à vista

As concessões de cartão de crédito à vista foram revisadas, a partir de julho de 2017, para ampliação de cobertura das estatísticas, com a inclusão de montantes concedidos diretamente por instituições de pagamento na modalidade cartão de crédito à vista de pessoas físicas.

Como resultado da revisão, as concessões de cartão à vista, em dezembro de 2019, passaram de R$102,8 bilhões (estatística divulgada em janeiro) para R$108,1 bilhões (estatística revisada). Essa revisão também impactou o saldo da modalidade, que passou de R$204,9 bilhões (estatística divulgada em janeiro) para R$215,6 bilhões (estatística revisada). Também houve impactos, pouco significativos, nos saldos de cartão de crédito rotativo e parcelado, dos montantes provenientes das instituições de pagamentos.

III) Concessões de cartão de crédito rotativo e parcelado

As concessões agregadas para crédito total e livre, pessoas físicas e pessoas jurídicas, foram revisadas, a partir de março de 2011, em função de aprimoramento metodológico que passou a excluir as concessões de cartão de crédito rotativo e parcelado. O objetivo da revisão foi eliminar a dupla contagem, posto que as concessões já foram consideradas, em sua quase totalidade, na modalidade de cartão à vista. As estatísticas de concessões de cartão de crédito rotativo e parcelado não foram alteradas por essa revisão, apenas seus montantes deixaram de ser considerados nas concessões agregadas.

IV) Impacto nas concessões agregadas

A tabela anexa resume o efeito conjunto das revisões acima mencionadas nas séries agregadas de concessões, em dezembro de 2019.

Os gráficos ao lado apresentam as estatísticas antes e depois da revisão, considerando tanto o valor das concessões quanto as taxas de variação do acumulado em 12 meses, para as concessões totais do SFN e do crédito livre.

4.3. Crédito ampliado ao setor não financeiro – dívida externa

A série de dívida externa de empresas que integra o crédito ampliado ao setor não financeiro foi revisada, desde março de 2018, a partir de reclassificação setorial de unidades institucionais, visando maior consistência com a estatística de dívida externa. Essa reclassificação implicou a exclusão do saldo de empréstimos e títulos de empresas que passaram a ser classificadas como intermediários financeiros. A melhoria na identificação do setor institucional deveu-se ao novo sistema de Registro Declaratório Eletrônico – Registro de Operações Financeiras (RDE-ROF), cuja implantação integral ocorreu em julho de 2019, que possibilitou superar limitações das bases de dados anteriores.

Como resultado da revisão, em dezembro de 2019, o total da dívida externa do setor privado não financeiro (Tabela 32-B) passou de R$1.384 bilhões (estatística divulgada em janeiro) para R$1.359 bilhões (estatística revisada). A revisão ocorreu em duas séries componentes: Empréstimos (de R$1.271 bilhões para R$1.270 bilhões) e Títulos emitidos no mercado externo (de R$104 bilhões para R$81 bilhões).

4.4. Outras revisões

Adicionalmente, foram feitas revisões, de reduzido impacto, nas seguintes estatísticas:

Saldo de crédito com recursos livres a pessoas jurídicas – antecipação de faturas de cartão: foram excluídas operações entre credenciadoras e bancos, que implicavam dupla contagem.

Saldo de crédito com recursos livres a pessoas físicas – crédito pessoal não consignado: reclassificação para essa modalidade, a partir dos saldos de "Outros créditos livres", devido à retificação das informações de algumas IFs.

Saldos de crédito por atividade econômica: reclassificação do setor de atividade de alguns tomadores, permitindo melhor avaliação econômica da destinação do crédito.

Concessões de crédito rural: aprimoramento das fontes de dados, que passam a incorporar informações diretamente fornecidas por cooperativas (ao invés de fornecidas pelos bancos cooperativos), implicando reclassificação entre pessoas físicas e jurídicas.

Prazo médio da carteira de crédito consignado: aumento dos prazos, nas estatísticas de 2013 a 2018, devido à revisão de dados por parte de algumas IFs.

Spread de operações de crédito com recursos livres: revisão do custo de captação das operações pós-fixadas referenciadas em índices de preços, devido a aprimoramento das fontes de dados.

Spread de operações de crédito com recursos direcionados: revisão do custo de captação dos financiamentos imobiliários (inclusão da remuneração do FGTS), do crédito rural e das operações pós-fixadas referenciadas em índices de preços, devido a aprimoramento das fontes de dados.

Comprometimento de renda das famílias: revisão das séries, a partir de janeiro de 2013, com aprimoramento da metodologia de estimação do custo médio das carteiras de crédito. Além disso, foram excluídas do cálculo as modalidades de desconto de cheques e microcrédito, por serem relacionadas a atividades produtivas.

DOCUMENTO: https://www.bcb.gov.br/content/estatisticas/docs_estatisticasmonetariascredito/Nota%20para%20a%20imprensa%20-%20Estat%C3%ADsticas%20Monet%C3%A1rias%20e%20de%20Cr%C3%A9dito.pdf

COMÉRCIO EXTERIOR BRASILEIRO

MRE. DCOM. NOTA-32. 21 de Fevereiro de 2020. Levantamento da suspensão das exportações de carne bovina in natura do Brasil pelos Estados Unidos

Hoje, 21 de fevereiro, o Serviço de Inspeção e Inocuidade Alimentar dos EUA anunciou a retirada da suspensão das exportações de carne bovina in natura do Brasil. A reabertura do mercado norte-americano às exportações de carne bovina “in natura” do Brasil, resultado de extenso processo de diálogo, troca de informações e inspeções técnicas, constitui um passo importante para projetar, no mercado internacional, a qualidade do produto brasileiro e do sistema de inspeção sanitária do País.

A reabertura do mercado norte-americano para as exportações brasileiras de carne bovina é exemplo concreto da solidez e do caráter mutuamente benéfico da parceria entre os governos dos dois países.

________________

LGCJ.: