US ECONOMICS

CHILE - ARGENTINA

U.S. Department of State. 10/31/2019. Briefing with Senior State Department Official on Argentina and Chile. Washington, D.C. Press Correspondents’ Room

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: It’s been a lively period in both Argentina and Chile. Lots of attention to the recent elections in Argentina, of course. They – between what they call the PASO primary season in August and then this past Sunday’s election, it went off with really, as far as I can tell, no complaints at all about the manner in which it was run. It was a very hard-fought election.

I think people believed it was going to be a much wider margin, but the president-elect won with a decisive margin and a – lacks a majority in his – the new congress, which will be seated later in the year. And so it’s clear that there’s a broad diversity of opinion in the political spectrum there. There’s a general sense and understanding that they face some serious economic challenges. And we’ve indicated, as we have all along, that we consider Argentina to be a good partner of the United States, an important trading partner. We have a lot of U.S. firms that are significant investors there and have been, really, for well over a century, some of these firms, and that there are great opportunities to work together in the energy sector and beyond.

The new incoming administration there has indicated that it will have some policy shift from what it was – from the outgoing Macri administration, but at the same time, they’ve made it exceptionally clear, both in their public conversations, or statements, and in their discussions with us and the transition team, that they are very much looking towards a very good working relationship and a good diplomatic relationship with the United States, and that they are looking for creating a framework for foreign investment, including U.S. investment, including in areas like Vaca Muerta, which is their Patagonian natural gas area. And so we look forward to continue working with Argentina.

Chile has had a – of course, I’m sure that you’ve all seen that they’ve had a difficult series of protests and challenges in recent days, that President Pinera has made some significant changes to his cabinet. He has announced what I think they call the new social agenda, trying to respond to the concerns that have been enunciated during the course of these protests. And yesterday, he made the difficult decision to cancel – in the context in which Santiago is living right now, to cancel the meetings – the leaders’ meeting of the – of APEC and the COP 25.

I think it’s important to keep in mind the positive agenda that Chile has had as steward of the APEC process over the last 12 months. And although we share with Sebastian Pinera, the president of Chile, regret that the meeting won’t go forward, you should take a look – I would recommend to you the agenda they’ve developed and the progress they’ve made in discussions on helping societies plan for aging populations, and so that they can make sure that there is an effective and equitable provision of social services that they focused on creating priorities for open and – an open trade agenda, which was very much in line with the priorities of this administration here in the United States, that they focused very much on promotion of small- and medium-sized business and entrepreneurship and inclusion of women in the economies of the APEC grouping – also something very much in line with our own agenda.

And so although circumstances have, as President Pinera said, obliged him to focus on Chile’s own domestic priorities at this moment, I think that they’ve developed an admirable record as presiding over the APEC process this year, and that process has produced a strong legacy.

MODERATOR: Okay. Matt’s not here to demand the first question, is he?

QUESTION: He’s the Matt for today.

MODERATOR: Oh, you’re AP. Okay. (Laughter.)

QUESTION: So I’m Matt today? Wow.

QUESTION: Oh, don’t say that.

QUESTION: I’m going to call my mom later and I’ll – (laughter) —

QUESTION: It’s Halloween.

MODERATOR: Big shoes to fill.

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: Nats win. (Laughter.)

QUESTION: Yeah, Nats win. Well, thank you for the honor. This is unprecedented. (Laughter.)

Is there – two questions, one on each, since you addressed both countries: Is there concern about how much influence in the government formula Cristina will have, how much influence she will have on Alberto?

And on Chile, is there indisputable evidence the U.S. has that Russia and foreign agents are sabotaging and trying to mess? I’ve seen press reports, but would like to make clear whether you are suspicious or whether the U.S. has hard evidence of Russia or any other – so in Latin America, the Venezuelan opposition talk about Maduro government as well. There are multiple allegedly perpetrators, but haven’t seen any evidence.

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: I – somebody actually sent me a snapshot of the ballot that was being cast at least in the city of Buenos Aires a couple of days ago, and it indicated that the candidate and the fellow who won the election was named Alberto Fernandez, and it was the vice president who was Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner. We look forward to working with the administration of Alberto Fernandez.

Obviously, and as he and others have said on the campaign trail, it’s a heterogeneous coalition of groups, and within his political party, his political movement, and each will have their say. But we’re looking forward to working with Alberto Fernandez and his administration.

If you look back to some of the comments we’ve made regarding the Russian influence on developments in Chile in recent days, what you’ll see is really a focus on the social media environment in which these have taken place. What’s going on in Chile, as the Chilean political leadership has recognized and as Chilean commentators have recognized, is fundamentally Chileans having a public – sometimes loud and, sadly, overly raucous – debate about Chilean issues. It has on the fringes, very lamentably and probably at high cost economically to the city of Santiago and elsewhere, included violence and arson and even some deaths.

What we’ve commented on regarding Russia is that we can see clear indications of people taking advantage of this debate and skewing it through the use and abuse of social media trolling and seeking – rather than allowing the citizens of Chile to have their own debate about how their country and the courses their country should take, they’ve sought to exacerbate divisions, foment conflict, and all around act as a spoiler to responsible democratic debate. That’s the problem.

QUESTION: And is that Russia or is it also Venezuela?

QUESTION: Maduro has done —

QUESTION: What are you seeing?

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: We have seen that indications that Russian – of Russian activity supporting this negative course of the debate. Am I saying that it’s a single point, that it’s (inaudible), all – that it’s the only factor involved, and the only outside factor? No, I’m not.

QUESTION: What – so what are the other factors? Are you saying Maduro, Venezuela? Are you saying Cuba?

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: You’re saying Venezuela and Cuba. (Laughter.)

QUESTION: Are you seeing – are you seeing that?

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: We are seeing – I will say, I certainly saw – and this is just on my personal observation. I am not a – I’m not a digital analytical wizard myself, but I certainly saw organizations such as Telesur exacerbating those debates, and anecdotally I can say that. But as far as any analysis we’ve done, I think I’ll just leave it where I’ve left it.

MODERATOR: Okay.

QUESTION: A question?

MODERATOR: Yeah.

QUESTION: Thank you.

QUESTION: Hi. Following up on that – L.A. Times – following up on that a little bit, to Luis’s question, you said you’re ready to work with the new Argentine government, and I know before the election some of your people from the embassy were starting to make contact. Can you tell – talk us to a little bit more about how much contact you’ve made with them already and at what levels?

And on Chile, I wondered if you were at all concerned at how quickly the rhetoric turned to – even from Pinera – of war and his quick turn to military. Given the history of that country, I wonder if that’s concerning to you.

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: I think I’ll take the last one first.

QUESTION: All right.

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: Simply to note that the Chilean Government has ended its – I don’t remember the legal term they use there, but it’s a state of emergency.

QUESTION: State of emergency, yeah.

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: And that I would – I have focused much more on the current expressions of willingness to have an open dialogue, the willingness to set a new legislative agenda and new priorities for his administration as an indication of the priorities of that government and that president. And I wouldn’t want – I wouldn’t pretend to speak for them.

We have relationships, we have diplomatic relationships with – and a robust embassy down in Buenos Aires. Some of these people have been in politics, some of the figures in this administration have been in public life – or the incoming administration, rather, have been in public life for many years. And so through the course of our diplomatic engagement with Argentina over the years, there are people in the State Department who’ve known some of them for 10, 15, 20, 25 years. The ones we’ve known for 25 years are surely vested in their pensions as we speak. (Laughter.)

And so it’s easy to have an open and free-flowing discussion with them. Some of them are – some of the advisors for President-elect Fernandez are members of the Argentine national congress. Others have been in elected positions in provinces. These are people that our mission would be talking to in the regular course of business long before the candidacy of Alberto Fernandez was even announced. So I think you can say with at least some of these people we’ve had very long engagement and discussions.

During the course of the campaign process, we’ve had the same kinds of conversations with them as we would have with any counterparts in any other country, any other democratic country in this hemisphere.

MODERATOR: Okay. Anybody? Go ahead.

QUESTION: Thank you. Beatriz Pascual with EFE. I wanted to ask a little bit broadly: How do you expect that the change of government in Argentina will impact the Lima Group? Because —

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: I can see, as any of you can see, the comments during the campaign. In their preliminary – excuse me, speaking in tongues – preliminary comments now that they are in the transition, that they criticize the administration of at least some – let me restate that. Let me start over. Some members of the transition group, some incoming elected officials who are – have been part of the Fernandez campaign have been sharply critical of Nicolas Maduro. Others have been less so, but have recognized the lack of democracy in Venezuela, and they’ve focused as well on the need for dialogue. On the campaign trail, Fernandez and others have said that they want to have a broader look at the kinds of dialogue that they need to have. I’ve heard different statements as to whether they would choose to do within the Lima Group or outside. We have urged them to do so from within the Lima Group.

Considering that it is – and we’re not a member of the Lima Group, remember – but it represents almost – almost, not all, but almost every democratic government in South America, and it represents that community of South American republics that are most exposed to the externalities of this crisis, the migration and public health crises. And even Argentina itself has hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans who have been displaced by what’s going on in Caracas, in Venezuela. And that’s an important grouping for South America.

MODERATOR: David.

QUESTION: Yeah, just wondering what formal contacts there have been with the president-elect of Argentina since the election. And is there any plan – I mean, has President Trump got any plans to talk to him that you’re aware of? Would that be in the normal course of events that they’d do that?

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: I think I can answer half of that. That’d perhaps be the normal course of events, but I don’t work at the White House. You’d have to take the rest – take that up with them.

MODERATOR: Good answer. (Laughter.)

QUESTION: But apart from that, have there been any formal interactions since the election?

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: We’ve been in contact both at the mission and beyond with his team.

MODERATOR: Shaun.

QUESTION: Can I just follow up on what you were mentioning with Russia, particularly talking about the social media trolling, et cetera? What do you think the motivation is? Is it simply a motivation to create chaos, in your view, or is there basically a policy direction that you see them wanting to achieve?

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: In recent years we’ve seen an increase of Russian engagement in the Americas, in South America in particular – very little of it positive. Starting from a very low base, and very little of it positive.

QUESTION: Is any of it positive?

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: Excuse me?

QUESTION: Is any of it positive? (Laughter.)

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: The goal – good quip, but I think I’ll just continue —

QUESTION: It was a question, too, so —

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: I’ll get to it, then. I’ll get to it. The – they seem to prefer a region divided, and they seem to prefer democratic debate mired in conflict, which is unfortunate. I’m sure there must be some positive engagement somewhere.

QUESTION: Just – sorry – to follow on the Russian involvement, are you seeing it elsewhere? And are you linking that Russian involvement on social media to specific groups or entities? Is it Kremlin-backed, Kremlin-tolerated? How does that work?

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: We’re attentive to the risks of this. I don’t think I’m going to go any farther than that for right now.

QUESTION: Is any of it, like, linked to Venezuela given the Russian closeness with the Maduro government?

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: I think I’ll refer back to the answer I gave to you.

QUESTION: Thanks.

QUESTION: And has Chile requested any cooperation from the U.S. in order to deal with these Russian trolls?

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: We have had —

QUESTION: Cyber security or cyber —

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: We’ve had a good and robust relationship with the Chilean Government for years, across administrations. Our public safety and public security agenda with them is broad and robust, and has been over the years very successful. So yeah, we talk to them about the challenges they’re facing now just as we have talked to them about working bilaterally and in the region for years.

MODERATOR: Go ahead.

QUESTION: Thank you.

MODERATOR: Said, I’m impressed.

QUESTION: Thank you. The perception is that you were slow to react to what was happening in Chile.

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: I’m sorry?

QUESTION: You were slow to react to the events in Chile.

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: We were slow to react?

QUESTION: Yes, you were slow to react, respond to these events, that your response would have been, let’s say a lot quicker if the government was not, let’s say, very close to the United States of America. That’s one. And sir, so what is your expectation that would happen over the next weeks, days?

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: From where we sit and work and from the engagements that we had immediately with our U.S. mission, particularly focused on the safety and welfare of U.S. citizens and on the general situation initially in metropolitan Santiago, I would not share that – the assertion of an impression of – I would regret that someone might have that impression. I certainly didn’t see it from where I sit.

The government of Sebastian Pinera and really all – met not so long ago with all political parties, and this opened up a social dialogue which has – which is continuing. It’s a very successful, robust democracy, accountable to its citizens. It had a tough – it’s had a tough couple of days, and they’ve recognized – in their own domestic sphere, they’ve expressed the intent to address the social challenges that they face. That’s how democracies work.

And if there was any difference in how we’ve – in the tone that you might – or others might – perceive, I think that’s, at root, the issue. We’re dealing with a robust democracy with a strong track record both socially and economically – but facing some serious challenges, and we deal with them with the respect that they deserve as a robust democracy.

QUESTION: I’m wondering if you have any comments on the accusations that there were some human rights violation during the repression of the protest.

SENIOR STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL: I know that they’ve invited the – they’ve thrown open the doors to inquiries. They’re conducting domestic inquiries, and they’ve thrown open the doors so that the UN Human Rights Commissioner – who also happens to be a Chilean – can send a team down. That seems like pretty responsible behavior, and we’ll see what those domestic and international inquiries produce.

MODERATOR: And where are you – I’m sorry. Which publication are you with?

QUESTION: Agence France Presse.

GDP

DoC. October 30, 2019. Economic indicators. Statement from U.S. Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross on Q3 2019 GDP Growth: U.S. Economy Grows 1.9 Percent in Third Quarter

Today, the Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) released the third quarter GDP growth number for 2019. The Bureau found that real gross domestic product increased at an annual rate of 1.9 percent in the third quarter.

“Today’s report shows that the U.S. economy continues its steady growth in defiance of media skeptics calling for a recession,” said Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross. “Since President Trump took office, wages have surged, unemployment has hit record lows, and poverty has fallen for all Americans, including the country’s most vulnerable.”

In the third quarter, U.S. consumer spending grew a healthy 2.9 percent, as American consumer confidence continued to buoy our country’s economic strength. Spending on durable goods led and jumped 7.6 percent from the second quarter. Business intellectual property investment rose 6.6 percent, signaling that American business will continue to lead the world with new ideas and inventions. The 1.6 percent growth in goods exports demonstrates that President Trump’s trade policies are bringing Made in America back.

This quarter’s growth number builds on a strong legacy of economic growth and accomplishments under President Donald Trump.

In September 2019, unemployment in the U.S. fell to 3.5 percent, hitting the lowest level in 50 years. The unemployment rate for Hispanic Americans and African Americans were also at record lows. The total numbers of employed Americans hit the highest level on record. Between 2017 and 2018, 2.3 million more Americans gained full-time, year-round employment, including 1.6 million women.

This has translated to higher incomes for average Americans. The Census Bureau reported in September that real median household income rose to more than $63,000 in 2018, the highest level in nearly two decades. Between 2017 and 2018, real median earnings of full-time, year-round workers rose 3.4% and 3.3% for men and women respectively. This good news tracks with Labor Department numbers, which marked more than a year of consecutive year-over-year hourly wage increases of 3.0 percent or higher. Before 2018, wage gains had not hit 3 percent since 2009.

The poverty rate has tumbled as well. In 2018, the poverty rate fell by 0.5 percent to the lowest level since 2001, as the growing economy lifted 1.7 million Americans out of poverty since just 2017. Disadvantaged groups such as Hispanic Americans and African Americans saw the largest poverty reductions. America’s children saw a 1.2 percentage points in poverty, while poverty for single mothers fell by 2.5 percentage points.

President Donald Trump’s economic and trade policies are delivering wins for the American people. A strong economy is lifting millions out of poverty and giving American workers long overdue pay increases.

PERSONAL INCOME

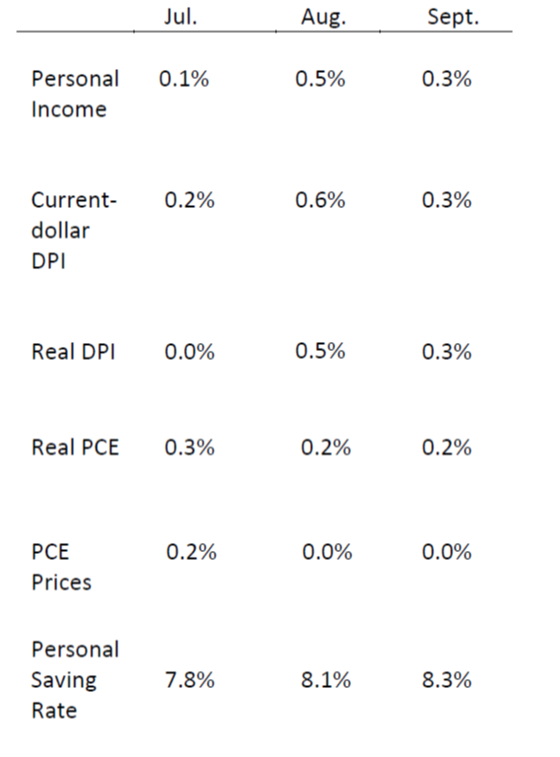

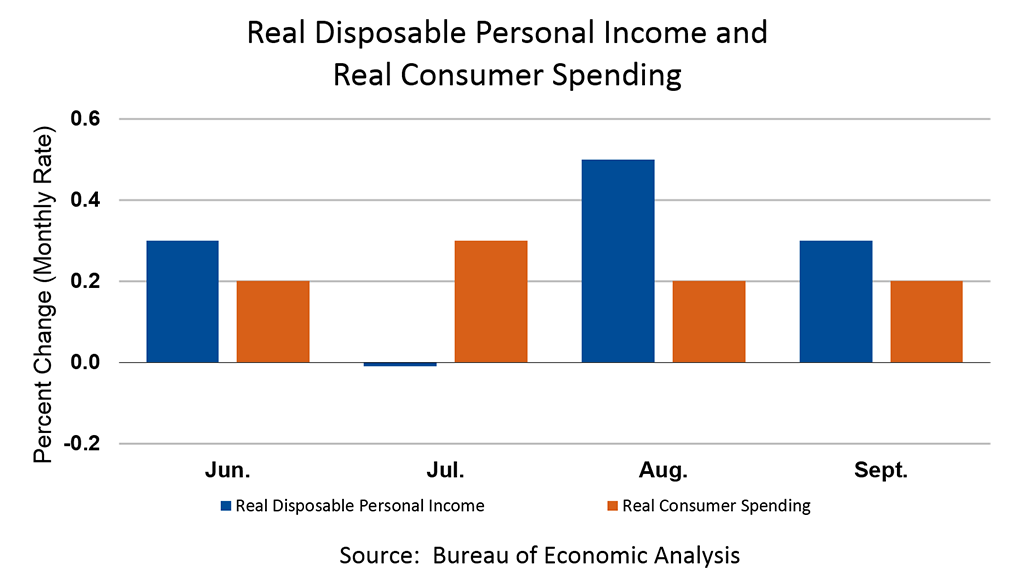

DoC. October 31, 2019. Real Disposable Personal Income Rises in September

Personal income increased 0.3 percent in September after increasing 0.5 percent in August. Wages and salaries, the largest component of personal income, showed no change in September after increasing 0.6 percent in August.

Current-dollar disposable personal income (DPI), after-tax income, increased 0.3 percent in September after increasing 0.6 percent in August.

Real DPI, income adjusted for taxes and inflation, increased 0.3 percent in September after

increasing 0.5 percent in August.

Real consumer spending (PCE), spending adjusted for price changes, increased 0.2 percent in September, the same increase as in August. Spending on durable goods increased 0.6 percent in September, the same increase as in August.

PCE prices were unchanged in September and in August. Excluding food and energy, PCE prices were

unchanged in September after increasing 0.1 percent in August.

Personal saving as a percent of DPI was 8.3 percent in September and 8.1 percent in August.

FULL DOCUMENT: https://www.bea.gov/system/files/2019-10/pi0919.pdf

APEC

U.S. Department of State. 10/31/2019. On the Cancellation of APEC Leaders’ Week Meetings and COP25 in Chile. Michael R. Pompeo, Secretary of State

We support Chilean President Sebastian Piñera who made the difficult decision to cancel the upcoming APEC Leaders’ Week Meetings and COP25 in Chile. We understand Chile’s decision to focus on national concerns, and are confident that the Chilean government and people will resolve ongoing protests with respect for free expression and human rights, within the framework of Chile’s strong, democratic institutions and rule of law. The United States is committed to continuing our longstanding relationship with Chile to promote security, prosperity, environmental stewardship, and good governance within our hemisphere and across the globe.

We recognize the leadership Chile has shown this year in advancing the goals of APEC and COP25. We are proud of our collective accomplishments over the past year in APEC, and we remain committed to working with our APEC partners to promoting free and open trade and investment in the Asia-Pacific region. We have appreciated working closely with them this year and look forward to future collaboration on these and other issues.

INDIA

U.S. Department of the Treasury. 11/01/2019. Joint Statement on the India – U.S. Economic and Financial Partnership

Indian Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman and U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Steven Mnuchin met in New Delhi to continue the India – U.S. Economic and Financial Partnership, a dialogue meant to deepen the economic partnership between the two countries and advance work in a number of areas to support economic growth and security. Following the conclusion of the dialogue, Indian Finance Minister Sitharaman and Treasury Secretary Mnuchin signed the following joint statement:

NEW DELHI – The Seventh Meeting of the Economic and Financial Partnership (EFP) was held in New Delhi on 1st November, 2019, between the Ministry of Finance of the Republic of India and the Department of the Treasury of the United States of America.

The Indian delegation was led by Smt. Nirmala Sitharaman, Minister of Finance, Government of India and the U.S. delegation was led by Mr. Steven Mnuchin, U.S. Secretary of the Treasury.

The Seventh Meeting of the India – U.S. Economic and Financial Partnership is meant to deepen the economic partnership between the two countries as a framework, commensurate with the growing importance of our economic relations and significant business and cultural ties that already exist between the two nations, and to undertake further work in a number of areas to improve cooperation and support for economic development. During this meeting of the EFP, both sides had in-depth exchanges of views on a range of issues such as the global, US, and Indian economic outlooks, global debt sustainability, financial sector reforms, leveraging of capital flows and investment, and tackling money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT).

India and the United States discussed policies to stimulate economic growth and noted the significant steps India has taken to strengthen the financial sector, including Public Sector Bank recapitalization and plans to merge some of the state-owned banks. Both sides also discussed capital flows, investment promotion related issues, and the external economic environment.

Both sides are committed to greater economic cooperation on global economic issues, both bilaterally and multilaterally in the G20 and other fora. India and the United States look forward to enhanced collaboration to address the challenges to global growth under the G20 Presidency of Saudi Arabia. As India gears up for the 2022 Presidency of the G20, the United States stands ready to support India in hosting a successful and focused Presidency.

Our respective financial regulatory authorities have also recently discussed financial regulatory developments in the Financial Regulatory Dialogue. The United States and India recently signed a Memorandum of Understanding for cooperation, coordination, consultation and exchange of information relating to the Regulation of the Insurance Sector. Both sides look forward to the ongoing discussion on issues related to data localization.

The United States and India recognize the importance of foreign portfolio investors for supporting economic growth, and discussed ways to build on India’s positive steps in further opening to greater foreign portfolio investment. Both sides welcome the growing bilateral foreign direct investment between our countries and underscore the importance of India taking steps to improve its investment climate for all types of investors. These investments will help to boost growth for both countries.

Both sides are working together to attract more private sector capital to finance India’s infrastructure needs and further raise growth for both countries. India has set up the National Infrastructure and Investment Fund (NIIF) to catalyze private institutional investment in Indian infrastructure, for which the United States has provided technical support. The United States helped the Indian city of Pune successfully launch municipal bonds in 2017 to finance local infrastructure needs to support the government’s Smart Cities initiative. India and the United States look forward to working together for preparing more cities to issue municipal bonds, including technical assistance, and to having a more broad-based relationship with respect to institutional investment into infrastructure in India.

Both sides took note of the importance of having greater attention to transparency and debt sustainability in bilateral development lending. India and the United States both support global efforts to improve debt sustainability and transparency, including through the international financial institutions’ multipronged approach and the efforts of the G20 and other groups. In 2019, India has voluntarily associated with the Paris Club to cooperate in its work, as an observer.

Both sides appreciated the recent signing of an arrangement that enables automatic exchange of Country-by Country Reports for purposes of high level transfer pricing risk assessment. Both sides also noted the significant progress in recent years to resolve bilateral tax disputes between the two countries, and applaud ongoing efforts to prevent tax disputes and provide certainty to taxpayers through the existing Mutual Agreement Procedure and bilateral Advance Pricing Agreement relationship.

India and the United States took note of the progress made in sharing financial account information between the two countries under the Inter-Governmental Agreement pursuant to the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA), and encourage both sides to work together to further improve the quality and usability of data for mutual benefit. Both sides will continue to collaborate and share experiences for tackling offshore tax evasion.

India and the United States will continue to enhance our cooperation in tackling money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT). Our relationship has strengthened over time as both sides have developed a holistic approach to our bilateral engagement on AML/CFT issues of shared concern. Our cooperation includes but is not limited to, information exchanges to combat global terrorist financing and to support the designation of specific terrorist facilitators and financiers, coordinating on AML/CFT and maintaining the integrity of the Financial Acton Task Force (FATF) global standards for AML/CFT. India has demonstrated its support for action against non-compliant countries. In addition, India and the United States continue to work on developing AML/CFT frameworks to mitigate the associated illicit finance risks.

Both sides are encouraged with the developments that have taken place since the last meeting of the Economic and Financial Partnership and look forward to continued engagement to strengthen our bilateral relationship, our economies and our economic security.

INTERNATIONAL TRADE

DoC. October 31, 2019. Secretary of Commerce Leads Trade Mission to the Indo-Pacific Region with Stops in Thailand, Indonesia, and Vietnam

WASHINGTON – U.S. Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross will lead a Business Delegation to the Indo-Pacific Business Forum in Bangkok, Thailand and subsequently to Indonesia and Vietnam from November 3 – 8, 2019. This mission supports President Donald J. Trump’s goals of accelerating U.S. commercial activity in the region, supporting job-creating export opportunities for American companies, as well as meeting the region’s needs for economic growth and development.

“At the Department of Commerce, we are working to fuel American private sector growth at home and in nations around the world,” said Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross. “With nearly $2 trillion in two-way trade in 2018, the Department is looking to cultivate key partnerships across the Indo-Pacific as U.S. companies are launching or expanding their businesses in these markets.”

Also included over the course of the trip are bilateral meetings with senior-level foreign government officials and business-to-business engagements that will advance specific commercial opportunities not only for mission participants, but also for the future of U.S. and Indo-Pacific trade.

MISSION STATEMENT: https://www.export.gov/article?id=IndoPacific-Mission-Statement-2019

GLOBAL ECONOMY

FED. November 01, 2019. Speech. The United States, Japan, and the Global Economy. Vice Chair Richard H. Clarida. At the Japan Society, New York, New York

I appreciate this opportunity to speak today at the Japan Society, a respected institution dedicated to studying, advocating, and expanding interactions between the United States and Japan.1 While the society's remit is broad and includes arts, culture, and education, I will, perhaps not surprisingly, focus my remarks on our two economies. Japan is an important economic partner of the United States, and our economies are linked through trade in goods and services as well as capital flows that affect interest rates and other aspects of financial markets. Through these channels, developments in Japan can affect economic conditions in the United States, and vice versa.

More broadly, beyond bilateral linkages, economic conditions in United States and Japan are tightly linked to global economic developments, and today I will discuss several of the global factors that are relevant to the outlook for both economies. First, I will review the current U.S. outlook and some key global risks to that outlook that we are monitoring at the Federal Reserve. I will next elaborate on the channels through which global factors affect domestic economic conditions in the United States and, in some cases, also Japan. I will conclude with some remarks about the monetary policy decision we announced on Wednesday.

U.S. Outlook

By many metrics, the U.S. economy is in a good place. The current economic expansion, now in its 11th year, is the longest on record, and the economy continues to advance at a moderate pace, with real gross domestic product (GDP) growth running at 2 percent over the past year and 1.9 percent in the most recent quarter. Growth has been supported by the continued strength of household consumption, underpinned, in turn, by a thriving labor market. The unemployment rate is near a half-century low, real wages are rising, and workers who had earlier left the labor force are returning to find jobs. There is no sign that cost-push pressures are putting excessive upward force on price inflation, and to me, plausible estimates of the natural rate of unemployment extend from just above 4 percent to the current level. Core personal consumption expenditures (PCE) inflation over the 12 months ending in September, at 1.7 percent, remains muted, and headline inflation, currently running at 1.3 percent, is likely this year to fall somewhat below our 2 percent objective. Price stability, as I see it, requires that inflation expectations as well as actual inflation be stable and consistent with our 2 percent inflation target. We do not directly observe inflation expectations, and I myself consult a wide range of survey and market estimates. Based on these estimates, I judge that measures of inflation expectations reside at the low end of a range I consider consistent with price stability.

Although the baseline expectation for the U.S. economy is favorable, there are some evident downside risks to this outlook. Global growth has been sluggish since the middle of 2018. This slowdown in global growth as well as increased uncertainty about the outlook for global trade policy appear to be headwinds for manufacturing activity and investment spending in the United States and abroad.2 Also another source of uncertainty in the global economy has been and continues to be Brexit. The global growth outlook also depends importantly on the strength and sustainability of continued economic expansion in China. China is balancing its desire to curtail credit growth and promote deleveraging against its understandable aspiration to maintain a rapid pace of economic growth in a country of 1.4 billion people. Finally, global disinflationary forces remain and present ongoing challenges to many central banks in their efforts to achieve and maintain price stability.

In sum, global conditions present headwinds for the U.S. outlook, and, as my colleagues and I at the Federal Reserve have emphasized, these headwinds have been a prominent consideration in our recent monetary policy assessments. I would now like to elaborate on some of the channels through which foreign developments more generally might be expected to affect the outlook for the U.S. economy.3

Channels and Linkages

Perhaps the most direct link between economic conditions abroad and in the United States is foreign demand for U.S. exports. To be sure, exports account for a smaller share of the U.S. economy—about 12 percent—than the global average of about 30 percent. Even so, when foreign demand for U.S. exports falls, the effect on U.S. production is evident. The pace of economic expansion abroad is a key determinant of the demand for U.S. exports. Most recently, the International Monetary Fund projects foreign GDP growth in 2019 to have slowed to its weakest pace since the financial crisis. Largely as a result, real U.S. exports been about flat over the past year, an unusual development outside of recession. U.S. exports also have slowed as a result of a decline in exports to China following the imposition of tariffs on U.S. goods and also more recently because of production-related disruptions in aircraft deliveries.

The pace of economic growth in our major trading partners affects the demand for U.S. exports not only directly, but also indirectly by influencing the value of the dollar. When foreign growth weakens and central banks abroad ease monetary policy to support their domestic economies, returns on dollar assets appear relatively more attractive, capital flows into U.S. markets, and these flows will tend to boost the foreign exchange value of the dollar. In addition, elevated uncertainties about the global outlook and/or other evidence of financial stress abroad can also drive up the value of the dollar, as investors flow into the safe haven traditionally provided by U.S. assets. A stronger dollar, for either reason, makes U.S. exports more expensive for foreign buyers, makes U.S. imports from abroad more attractive to U.S. purchasers, and thereby tends to lower demand for U.S. goods and services. That being said, I would note that the value of the dollar does not appear to play much of a role in explaining the decline in sharp slowdown in U.S. exports over the past year. The current level of the trade-weighted dollar is about where it has been, on average, over the past few years. However, looking back several years, the 25 percent appreciation of the dollar that occurred in 2014 was an important contributing factor to the previous noticeable decline in U.S. exports that took place in 2015 and 2016.

Global financial markets also link the United States to the global economy, and developments abroad can spill over into domestic financial conditions, with material effects on domestic activity. This is particularly evident during episodes of global financial stress, in which "risk-off" shifts in sentiment can depress U.S. equity prices and widen domestic credit spreads even as flight-to-safety flows push down U.S. Treasury yields. These global financial spillovers to the U.S. economy were notably pronounced during the 1998 Russian crisis, the euro-area debt crisis earlier this decade, and the China devaluation episode of 2015–16. Recently, global financial spillovers have contributed to the significant decline in U.S. Treasury yields that we have seen since the spring. Since the market for debt is global, low—and, in many cases, negative—yields abroad encourage capital inflows that put downward pressure on U.S. yields. Equity prices have also reacted to global developments and recently appear particularly sensitive to news about the outlook for U.S. international trade. Global factors have likely also contributed to the estimated decline in the neutral rate of interest, or r*, that we have observed in the United States and many other countries. Slow productivity growth and population aging have lowered potential growth rates in major foreign economies, decreasing demand for investment and increasing desired saving, both of which have contributed to lower equilibrium interest rates abroad, with spillovers to the rest of the world, including in the United States.4

Global developments influence not only U.S. economic activity and financial markets, but also U.S. inflation. Global factors—through their influences on U.S. aggregate demand and supply that I just described—can alter U.S. inflation dynamics. Foreign factors can also directly affect the prices paid by U.S. firms and consumers, particularly, but not exclusively, for imported goods. An appreciation of the dollar can lower the dollar price of U.S. imports, although empirically, this effect is less than one-for-one, as foreign exporters tend to keep the dollar prices of their goods comparatively stable relative to observed exchange rate fluctuations.5 In addition, swings in global commodity prices influence U.S. inflation. Over the past year, the rise in the dollar and falling oil prices have been important contributors to the subdued pace of U.S. inflation.

Japan in the Global Economy

Up to now, I have focused on the U.S. economy. However, despite some important differences that I will note, the Japanese economy exhibits some notable similarities to the United States, both in terms of its overall performance and its exposure to the global economy. To begin with, Japanese growth, while slower than in the United States, has been running above the pace needed to absorb new entrants to the labor force, and its strong labor market is operating with an unemployment rate near multidecade lows at 2.2 percent. Also, as in the United States, weak exports have recently been a drag on Japanese growth. But, like the United States, Japan has been less exposed to the global slowdown than many other economies. Exports represent only 17 percent of Japanese GDP, higher than in the United States but well below the 30 percent global average I mentioned earlier.

In some respects, however, Japan is more strongly linked to the global economy than is the United States. One example is the relationship between episodes of global financial stress and the exchange rate. In times of stress, the dollar tends to appreciate as investors seek the safety of U.S. markets. The same is even more true for Japan, with the yen often recording even stronger appreciation than the dollar in times of increased risk aversion.

Other channels operate differently because of structural differences between the United States and Japan. One difference is in the currency used to invoice trade. In the United States, almost all trade, both imports and exports, is invoiced in dollars. One aspect of this, as mentioned earlier, is that changes in the value of the dollar tend to have a relatively limited effect on U.S. import prices and import demand. Despite the importance of the yen in global financial markets, a significant portion of Japan's trade is also invoiced in dollars rather than yen, including not only Japan's exports to the United States, but also its exports to other countries in Asia.6 Some scholars have proposed that the importance of the dollar in Japan's trade lessens the responsiveness of Japan's exports to movements in the yen while making exports more sensitive to changes in the value of the dollar and, therefore, U.S. monetary conditions.7

Regarding inflation, through the considerable efforts of the Bank of Japan's quantitative and qualitative monetary easing program launched in early 2013, Japan has emerged from almost 15 years of modest deflation and is now operating with a positive inflation rate. While the inflation remains below the Bank of Japan's long-run objective of 2 percent, it represents a notable accomplishment given the difficulty of changing public inflation expectations after a long period of modest deflation in consumer prices.

Conclusion

Returning to the United States, I would like to wrap up with a brief discussion of our monetary policy decision this week. At our meeting earlier this week, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) lowered the target range for the federal funds rate by 1/4 percentage point, bringing the range to 1-1/2 to 1-3/4 percent—the third such reduction this year.8 As Chair Powell noted in his press conference, the Committee took these actions to help keep the U.S. economy strong in the face of global developments and to provide some insurance against ongoing risks. The policy adjustments we have made since last year are providing—and will continue to provide—meaningful support to the economy. The economy is in a good place, and monetary policy is in a good place.

The policy adjustments we have made to date will continue to provide significant support for the economy. Since monetary policy operates with a lag, the full effects of these adjustments on economic growth, the job market, and inflation will be realized over time. We see the current stance of monetary policy as likely to remain appropriate as long as incoming information about the economy remains broadly consistent with our outlook of moderate economic growth, a strong labor market, and inflation near our symmetric 2 percent objective. Of course, if developments emerge that cause a material reassessment of our outlook, we would respond accordingly. Policy is not on a preset course, and we will be monitoring the effects of our policy actions, along with other information bearing on the outlook, as we assess, at each future meeting, the appropriate path of the target range for the federal funds rate.

Thank you very much for your time and attention and for the invitation to speak at the Japan Society this afternoon.

Notes

- These remarks represent my own views, which do not necessarily represent those of the Federal Reserve Board or the Federal Open Market Committee. I would like to thank Joseph Gruber for his assistance in preparing this speech.

- Caldara and others find that increased trade policy uncertainty, independent of the actual effect of higher tariffs, can exert a significant negative drag on U.S. and global GDP. See Dario Caldara, Matteo Iacoviello, Patrick Molligo, Andrea Prestipino, and Andrea Raffo (2019), "The Economic Effects of Trade Policy Uncertainty (PDF)," International Finance Discussion Papers 1256 (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, September).

- For further discussion, see Richard H. Clarida (2019), "Global Shocks and the U.S. Economy," speech delivered at the BDF Symposium and 34th SUERF Colloquium, sponsored by Banque de France and the European Money and Finance Forum, Paris, March 28.

- See Richard Clarida (2019), "The Global Factor in Neutral Policy Rates: Some Implications for Exchange Rates, Monetary Policy, and Policy Coordination (PDF)," International Finance Discussion Papers 1244 (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, April). For one example highlighting demographics, see Etienne Gagnon, Benjamin K. Johannsen, and David Lopez-Salido (2016), "Understanding the New Normal: The Role of Demographics (PDF)," Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2016-080 (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, October).

- See José Manuel Campa and Linda S. Goldberg (2005), "Exchange Rate Pass-Through into Import Prices," Review of Economics and Statistics, vol. 87 (November), pp. 679–90; and Christopher Gust, Sylvain Leduc, and Robert Vigfusson (2010), "Trade Integration, Competition, and the Decline in Exchange-Rate Pass-Through," Journal of Monetary Economics, vol. 57 (April), pp. 309–24.

- See Takatoshi Ito, Satoshi Koibuchi, Kiyotaka Sato, and Junko Shimizu (2019), "Growing Use of Local Currencies in Japanese Trade with Asian Countries: A New Puzzle of Invoicing Currency Choice," Vox, June 10.

- See Gita Gopinath, Emine Boz, Camila Casas, Federico J. Diez, Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, and Mikkel Plagborg-Møller (2019), "Dominant Currency Paradigm," NBER Working Paper Series 22943 (Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research, March).

- See Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2019), "Federal Reserve Issues FOMC Statement," press release, October 30.

FULL DOCUMENT: https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/files/clarida20191101a.pdf

ECONOMY

FED. November 01, 2019. Speech. Friedrich Hayek and the Price System. Vice Chair for Supervision Randal K. Quarles. At "The Road to Serfdom at 75: The Future of Classical Liberalism and the Free Market" Ninth Annual Conference of the William F. Buckley, Jr., Program at Yale, New Haven, Connecticut

I am delighted to be back in New Haven and particularly to be in the company of so many students interested in thinking rigorously about ideas. And I am honored to be participating in the William F. Buckley, Jr., Program's conference today on Friedrich Hayek and the future of classical liberalism.1

Over the course of this afternoon, you will hear a series of presentations that put Hayek's thinking in the context of contemporary developments and that offer a variety of perspectives on his intellectual legacy. Hayek was a prolific—some might even say profligate—thinker. He was at various times, and in various modes, an early neuropsychologist, an epistemologist, a theoretical economist, a political philosopher, a moral philosopher, a philosopher of science, a historian of ideas, a public intellectual, and a social polemicist. This vast range has caused some to undervalue his contributions as an economist, notwithstanding his eventual Nobel Prize—when Hayek moved to the United States in 1950, the University of Chicago Economics Department would not hire him because, as Milton Friedman said, "At that stage, he really wasn't doing any economics," and Paul Krugman famously said that "the Hayek thing is almost entirely about politics, not economics."2 Others believe his broader thought, while seminal, was inconsistent across these various areas, and Hayek himself never demonstrated how it all hung together. In my contribution to the discussion today, I want to examine a particular example of the lasting effect that Hayek has had on economic thinking—one pertaining to the importance of freely determined prices for producing efficient economic outcomes—and consider how Hayek's insights in this area can, in fact, tie together the various strands of his larger philosophy.

So as not to appear entirely out of touch with more immediate developments, I will end by descending from the empyrean to the terrestrial with a discussion of the economic outlook and the Federal Open Market Committee's (FOMC) policy decision from earlier this week.

Hayek and Economics

Hayek's contributions to economics ranged widely, and many were important and of lasting influence. Among them were his studies of the relationship between the economic and political arrangements of a society. That body of work included, of course, his celebrated book The Road to Serfdom, which was published 75 years ago this year and is a focus of this event, as well as his later monograph, The Constitution of Liberty.3 In addition, Hayek contributed prominently to monetary analysis. His work in this area included the theory of the business cycle that was part of the thinking of the Austrian school of economics.4 It also included Hayek's studies of the feasibility and implications of private-sector currency issuance—contributions that have informed modern-day analyses of the repercussions of electronic money.5

Today, however, I will be concerned instead with still another key contribution that Hayek made to economic analysis: understanding the operation of the price system. This contribution was formalized in his most famous paper in the economic-research literature: his article "The Use of Knowledge in Society," which was published in the American Economic Review in September 1945.6

Hayek (1945) Revisited

It is worth outlining the basis for the high esteem in which economists hold Hayek's 1945 contribution. In 1974, the press release by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences that announced Hayek's Nobel Prize in Economics stated: "The Academy is of the opinion that von Hayek's analysis of the functional efficiency of different economic systems is one of his most significant contributions to economic research in the broader sense. ...His guiding principle when comparing various systems is to study how efficiently all the knowledge and all the information dispersed among individuals and enterprises [are] utilized. His conclusion is that only by far-reaching decentralization in a market system with competition and free price-fixing is it possible to make full use of knowledge and information."7

In the research that the academy described, Hayek's 1945 paper was the key article. More recently, this paper received further prominent acclaim when it was categorized by an expert panel as being one of the top 20 articles ever published in the American Economic Review.8

With regard to the paper's contribution to the understanding of economic processes, an illuminating discussion was provided in 2005 by Oliver Williamson—himself later a Nobel laureate in economics. Williamson cited Hayek's 1945 paper, along with Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations from the eighteenth century, as forming the core of a "venerated tradition in economics" of studying the notion of "spontaneous order" arising from a freely operating market system.9

How does Hayek's case for the price system fit in alongside the other work that Williamson mentioned? As Paul Samuelson—yet another Nobel Prize winner—had occasion to note, the argument for the price system that Hayek articulated in 1945 was complementary with, but distinct from, the argument that Adam Smith espoused in The Wealth of Nations.10 Smith focused on how market mechanisms guide producers toward satisfying consumers' wants. Hayek instead stressed how the market mechanism makes, as he put it, "fuller use...of the existing knowledge" than a directed economy is able to do.11

Hayek emphasized that the signals transmitted by the various individual prices in the economy could, together, serve as a useful means of guiding overall resource allocation. The reason is that prices convey messages to consumers and producers even when the information that drives prices is not aggregated or directly observed.12 For example, a large increase or decrease in the price of gasoline conveys information that influences consumer behavior and that also affects the behavior of energy producers, even when neither of these sets of market participants are aware of the precise factor initiating the price change. As a related matter, Hayek recognized that prices transmit information even in a situation in which much of that information is not explicitly disclosed by one market participant to another, or even consciously articulable by any market participant at all. Hayek believed that all of us "know" many things that we cannot articulate but that we nevertheless act on in practical situations, and the price system can therefore aggregate and transmit that knowledge which we could not otherwise convey.

Hayek's analysis had implications for the viability of different economic systems. With regard to centrally planned economic systems—which had considerable support in the West in 1945, in light of the increased use of government economic controls in many countries during World War II and the dismal performance of market economies during the Great Depression—Hayek's analysis suggested that these systems would likely exhibit great inefficiency. To Hayek, it was totally unrealistic to expect an economy to operate efficiently if it was based on the "direction of the whole economic system according to one unified plan," as such a plan lacked the valuable information embedded in market-determined prices.13

The economist Gregory Mankiw has elegantly summed up Hayek's insight here: "Information is very, very dispersed among the population. ...Nobody can possibly know all the information you need to run a centrally planned economy."14 Hayek's economic analysis therefore complemented the philosophical and political arguments he marshaled against centrally planned economies in The Road to Serfdom. Again, it is important to recognize that this is not a contingent or technological problem. It is not only that the dispersion of knowledge makes it hard to gather, although that is certainly true—but if that were the only issue, then perhaps future advances in technology such as quantum computing would remove that obstacle. Rather, as already mentioned, we all know many important things that we cannot articulate; and many of these things we come to know precisely through our participation in trade and exchange through the market. This type of knowledge (a) is by its nature not conveyable to a central planner because we are not fully aware of all we know, and (b) would not even exist apart from the social interactions facilitated by the market which a central planner would replace.

The flip side of Hayek's analysis was that, while there are insurmountable obstacles to economic efficiency via a central plan, an efficient economy may still be obtainable by letting the price system work. To quote Mankiw again, Hayek's analysis implies that "markets figure out a way to aggregate, in a decentralized way, dispersed information into desirable outcomes."15 Furthermore, this mechanism does not require the government or any one individual to process that dispersed information into a central network or to be able to aggregate the information into a statistical series. It is, instead, sufficient for the proper operation of the price mechanism that the relevant information be embodied implicitly in the economy's multiplicity of prices of individual goods and factors of production. This information is recorded in such prices because they respond to the behavior of individual buyers and sellers in the economy.16 Consequently, as longtime Hayek scholar Gerald O'Driscoll has observed: "What particularly recommends the price system to Hayek is the 'economy of knowledge' with which it operates. It is [in Hayek's description] nothing short of a 'marvel.' "17

How Hayek (1945) Has Influenced Economics

Hayek's 1945 paper has had a great influence on subsequent economic research. It has been found to be highly relevant to a variety of areas of economic inquiry. For example, Hayek's analysis has proved valuable in the development of standard microeconomics, since his contribution deepened economists' understanding of the working of the price system and promoted further investigation of the question of how decentralized information is transmitted by markets.18 Hayek's emphasis on prices as processors of information has also had applications to international trade theory.19 And in macroeconomics and monetary theory, Milton Friedman's Nobel lecture, published in 1977, cited Hayek's 1945 paper when arguing that, because it disrupted the signals arising from relative-price movements, inflation both lowered the efficiency of the economy and led output to deviate from its natural (or full-employment) level.20 Hayek likened the price mechanism to a "system of telecommunications," and Friedman's description of inflation as a form of "static" interrupting price signals was in keeping with this analogy.21

Hayek's ideas on prices influenced Joseph Stiglitz in his analysis of markets with asymmetric information and Roger Myerson's insights on mechanism design theory. Each of these bodies of work earned a Nobel Prize.22

Qualifications and Extensions

I do not want to leave the impression, however, that all of the conclusions in Hayek's 1945 paper have become unchallenged principles chiseled into the economic consensus. On the contrary, one of the reasons why the paper has been so influential is that it remains a benchmark reference for understanding the case for relying primarily on a market system, based on freely determined prices, for determining the production and allocation of resources. The paper has therefore set a high bar for preempting the price system or for other interventions in the market: When economists point to cases in which market mechanisms can be improved on by regulation or other public-sector intervention, or to instances in which price signals do not appear to be operating effectively, they need to identify a specific market failure as the source of the inefficiency. Essentially, they need to establish instances in which the price system can be improved on as a means of processing information.23

Even Hayek acknowledged that the price mechanism works within an ecosystem of laws and social institutions, and those may evolve in ways that interfere with the signaling of prices. For example, one of the important events that raised doubts about the functioning of the private market's pricing process occurred in the years leading up to the financial crisis. This period featured pricing by financial markets that seemed, in some prominent cases, not to be adequately reflecting information about actual risks. Spreads on risky private-sector debt reached very low levels, and damaging spillovers to the nonfinancial sector occurred in the form of unduly high real estate prices and excessive leverage by borrowers in the housing market. One of my predecessors at the Federal Reserve Board, Donald Kohn, has noted the seeming herd-like behavior of financial markets in the pre-crisis period that generated this situation—an "underpricing of risk."24

The financial crisis, and the deep recession that followed it, prompted changes in the United States' regulatory framework. These changes have been designed to make the financial system more resilient than it was before the crisis. By creating appropriate incentives and rules, they should also encourage financial markets to price risk more appropriately than they did in the years leading up to the crisis—for example, by reducing the danger of investor complacency regarding the riskiness of their investments and the possibility of adverse scenarios. If we follow Hayek and regard the price system as like a telecommunications network, and then apply that metaphor to the financial sector, we can think of the institutional and regulatory changes to the financial system over the past decade as designed to improve the reliability and signal quality of the transmissions.25

How does all of this relate to the larger questions of philosophy and social order to which Hayek devoted much of his thought? Hayek's insights about the price system depend importantly on his theory of knowledge: The information that is available to us as a society is the aggregate of the highly dispersed and sometimes inarticulate knowledge possessed by each of us individually. It is not only hard to convey that information to a central authority for processing into a rational decision—it is also conceptually impossible given the nature of that knowledge. And, indeed, important parts of that knowledge will not even be generated except through our interaction with each other through the mechanism of the market. Trying to centralize economic decisionmaking, then, is not just too hard to do as a practical matter. It would actually reduce the amount of knowledge available to us as a society, by replacing those myriad individual interactions in a free marketplace. Thus, even if some technological way to aggregate information other than through prices could be invented, it would lead to less efficient, less humane outcomes because it would be based on less total human information. The price mechanism, then, is not just a matter of economics—it is a matter of social and, indeed, civilizational progress. As Hayek says in The Constitution of Liberty, "[C]ivilization begins when the individual in pursuit of his ends can make use of more knowledge than he himself acquired and when he can transcend the boundaries of his ignorance by profiting from knowledge that he himself does not possess."26 I think this ties together the various threads of Hayek's thought throughout a long life: his early work on psychology ("How do we know?"), his later epistemology ("What do we know, and what does it mean to know it?"), his economics ("How do we make knowledge usable?"), and his social and political theory ("What institutions will ensure that the greatest amount of human knowledge will be usable in the pursuit of their human fulfillment?"). Contrary to those polemicists across the ideological spectrum whose tendentious simplifications of Hayek's thought would turn him into a crude icon rather than a complex thinker, this is a deeply human, and a deeply humane, project. I will look forward to the contributions of the others you will hear from today in how Hayek elaborated it and how we can further these principles today.

Economic Outlook and Monetary Policy

Now I would like to turn to the current economic scene and this week's FOMC decision. Let me start by saying that the U.S. economy is doing well, and I am optimistic about the outlook. Economic conditions are currently very close to meeting our—that is, the FOMC's—dual-mandate objectives of maximum sustainable employment and price stability.

A particular source of strength has been the labor market. Setting aside the monthly volatility and, specifically, the effects of the recent strike at General Motors, labor market indicators are as strong as they have been in quite some time. The unemployment rate has been running near a 50-year low, and the proportion of the population currently employed is close to its highest level in a decade. Encouragingly, labor force participation has held up, as the tight labor market has motivated workers to either join or remain in the labor force, halting, at least for the time being, a long-standing downward trend. Although the pace of job gains has slowed this year, we expected some deceleration because of how low the unemployment rate has fallen.

A strong job market and high employment have in turn supported economic growth. Personal consumption expenditures (PCE) grew 2-1/2 percent over the past four quarters, a healthy pace by historical standards and a major contributor to overall growth since consumption represents over two-thirds of economic activity. Because the labor market remains tight, I expect wage growth to pick up, which would then in turn underpin further strength in consumption and overall growth.

For the other half of our mandate, inflation as measured by the PCE index was 1.3 percent over the 12 months ending in September, while core PCE inflation, which excludes increases in the prices of food and energy, was 1.7 percent. While these readings are below our 2 percent inflation objective, they are fairly close, and my assessment is that inflation will inch toward our objective in the coming months.

Outside the near term, I am also optimistic about the longer-term potential of the U.S. economy. I am heartened by a recent pickup in labor productivity growth. A notable development of the post-crisis period has been the abysmal pace of labor productivity growth. After averaging about a 2-1/4 percent pace in the two decades leading up to the crisis, labor productivity growth has been closer to 1 percent, on average, since 2011. While there has been much speculation, it remains to be seen what has driven this slowdown. Consequently, the slowdown could resolve unpredictably. Although the quarterly data are volatile, I have been encouraged by a pickup in labor productivity in the first half of this year, when it grew at a 3 percent annual rate. Further out, I admit to being a bit of techno-enthusiast, and I see the potential for many emerging technologies, including 5G communications, artificial intelligence and machine learning, and 3-D printing, to further boost productivity growth in the coming years.

Having established my optimism, I will now circle back to some more worrying signs in the recent data that suggest some headwinds are holding back growth. One prominent factor weighing on a relatively robust domestic economy has been weak growth among our trading partners. The International Monetary Fund projects that global economic growth in 2019 will be the slowest since the financial crisis. Partly as a consequence of weak foreign growth, U.S. exports have been flat over the past year.

Another weak spot has been investment. After a strong 2017 and start to 2018, business fixed investment has tailed off this year and fallen outright in the second and third quarters. I find the weakness of investment to be of particular concern because increasing investment and the capital stock are important for raising the potential capacity of the economy. It is likely that some of the weakness in capital spending is a result of elevated uncertainty, for foreign growth generally but also specifically for trade developments.

Against this backdrop, at our meeting earlier this week, we decided to lower our target range for the federal funds rate for the third time this year. We took this action to help keep the U.S. economy strong in the face of global developments and to provide some insurance against ongoing risks. By lowering the federal funds rate this year, we are supporting the continued expansion of the economy. Overall, with these policy adjustments, I believe that the economy will remain in a good place, with the labor market remaining strong and inflation staying close to our 2 percent objective. We see the current stance of monetary policy as likely to remain appropriate as long as incoming information about the economy continues to be broadly consistent with our outlook of moderate economic growth, a strong labor market, and inflation near our symmetric 2 percent objective.

References

- Arrow, Kenneth J., B. Douglas Bernheim, Martin S. Feldstein, Daniel L. McFadden, James M. Poterba, and Robert M. Solow (2011). "100 Years of the American Economic Review: The Top 20 Articles," American Economic Review, vol. 101 (February), pp. 1–8.

- Arrow, Kenneth J., and Gerard Debreu (1954). "Existence of an Equilibrium for a Competitive Economy," Econometrica, vol. 22 (July), pp. 265–90.

- Bernhofen, Daniel M., and John C. Brown (2004). "A Direct Test of the Theory of Comparative Advantage: The Case of Japan," Journal of Political Economy, vol. 112 (February), pp. 48–67.

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2019). "Minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee, July 30–31, 2019," press release, August 21.

- Brainard, Lael (2019). "Digital Currencies, Stablecoins, and the Evolving Payments Landscape," speech delivered at "The Future of Money in the Digital Age," a conference sponsored by the Peterson Institute for International Economics and Princeton University's Bendheim Center for Finance, Washington, October 16.

- Brunnermeier, Markus K., Harold James, and Jean-Pierre Landau (2019). "The Digitalization of Money," paper presented at "The Future of Money in the Digital Age (PDF)," a conference held at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, Washington, October 16.

- Caldwell, Bruce (2004). Hayek's Challenge: An Intellectual Biography of F.A. Hayek. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ——— (forthcoming). "The Road to Serfdom after 75 Years," Journal of Economic Literature.

- Cassidy, John (2000). "The Price Prophet," New Yorker, February 7, pp. 44–51.

- Dasgupta, Partha (1980). "Decentralization and Rights," Economica, vol. 47 (May), pp. 107–23.

- Fernández-Villaverde, Jesús, and Daniel Sanches (2019). "Can Currency Competition Work?" Journal of Monetary Economics, vol. 106 (October), 1–15.

- Friedman, Milton (1977). "Nobel Lecture: Inflation and Unemployment," Journal of Political Economy, vol. 85 (June), pp. 451–72.

- Friedman, Milton, and Rose Friedman (1980). Free to Choose: A Personal Statement. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- Hayek, Friedrich A. (1935). Prices and Production, 2nd ed. London: G. Routledge and Sons.

- ——— (1944). The Road to Serfdom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ——— (1945). "The Use of Knowledge in Society," American Economic Review, vol. 35 (September), pp. 519–30.

- ——— (1960). The Constitution of Liberty. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ——— (1976). "Denationalisation of Money: An Analysis of the Theory and Practice of Concurrent Currencies," Hobart Paper 70. London: Institute of Economic Affairs, October.

- Kohn, Donald L. (2009). "Comments on 'Financial Intermediation and the Post-Crisis Financial System,' " speech delivered at the Eighth BIS Annual Conference 2009, Financial System and Macroeconomic Resilience: Revisited, Basel, Switzerland, July 10.

- Krugman, Paul (2011). "Things That Never Happened in the History of Macroeconomics," New York Times, The Conscience of a Liberal (blog), December 5.

- Lucas, Robert E., Jr. (2004). "Keynote Address to the 2003 HOPE Conference: My Keynesian Education," History of Political Economy, vol. 36 (supplement), pp. 12–24.

- Mankiw, N. Gregory (2017). "N. Gregory Mankiw: America's Economy and the Case for Free Markets," Conversations with Bill Kristol, interview, April 9, YouTube video, 1:06:03, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QY4M6a56nFs.

- Myerson, Roger B. (2008). "Perspectives on Mechanism Design in Economic Theory," American Economic Review, vol. 98 (June), pp. 586–603.

- O'Driscoll, Gerald P., Jr. (1977). Economics as a Coordination Problem: The Contributions of Friedrich A. Hayek. Kansas City, Mo.: Sheed Andrews and McMeel.

- Quarles, Randal K. (2019). "The Financial Stability Board at 10 Years—Looking Back and Looking Ahead," speech delivered at the European Banking Federation's European Banking Summit, Brussels, October 3.

- Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences (1974). "Economics Prize for Works in Economic Theory and Inter-Disciplinary Research," press release, October 9.

- Samuelson, Paul A. (1983). "My Life Philosophy," American Economist, vol. 27 (Fall), pp. 5–12.

- Serrano, Roberto (2002). "Decentralized Information and the Walrasian Outcome: A Pairwise Meetings Market with Private Values," Journal of Mathematical Economics, vol. 38 (September), pp. 65–89.

- Smith, Adam (1776). An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, 5th ed., Edwin Cannan, ed., 1930. London: Methuen and Co.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (2000). "The Contributions of the Economics of Information to Twentieth Century Economics," Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 115 (November), pp. 1441–78.

- Taylor, John B. (2012). "Why We Still Need to Read Hayek (PDF)," speech delivered at the Hayek Lecture, New York, May 31.

- Williamson, Oliver E. (2005). "The Economics of Governance," American Economic Review, vol. 95 (May, Papers and Proceedings), pp. 1–18.

- Woodford, Michael (2003). Interest and Prices: Foundations of a Theory of Monetary Policy. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- Yellen, Janet L. (2017). "Financial Stability a Decade after the Onset of the Crisis," speech delivered at "Fostering a Dynamic Global Economy," a symposium sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, held in Jackson Hole, Wyo., Aug. 24–26.

Notes

- All of my remarks today represent my own views, which do not necessarily represent those of the Federal Reserve Board, the Federal Open Market Committee, or the Financial Stability Board. I would like to thank Ed Nelson for his assistance in preparing these remarks.

- See, respectively, Cassidy (2000) and Krugman (2011).

- See Hayek (1944, 1960). For an extensive analysis of these books, see Caldwell (2004) and, more recently, Caldwell (forthcoming).

- See, for example, Hayek (1935). For an examination of this body of work, see O'Driscoll (1977).

- See especially Hayek (1976). For recent formal investigations of the topic, see Brunnermeier, James, and Landau (2019) and Fernández-Villaverde and Sanches (2019). My Board colleague, Lael Brainard, has recently discussed the policy implications of electronic money. See Brainard (2019). The potential implications of privately issued currency in the form of stablecoins are under active consideration by the Financial Stability Board, which I chair, in work to be delivered to the Group of Twenty later next year.

- See Hayek (1945).

- See Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences (1974, paragraph 10).

- See Arrow and others (2011, p. 4).

- See Williamson (2005, p. 1). This discussion referred to Smith (1776) and Arrow and Debreu (1954) alongside Hayek (1945).

- See Samuelson (1983, p. 6).

- The quotation is from Hayek (1945, p. 521).

- Hayek's analysis therefore differed from general equilibrium approaches to economic problems, exemplified by the work of Arrow and Debreu (1954). Such approaches tend to evaluate market outcomes in terms of their ability to reproduce the allocation decided on by a hypothetical social planner who possesses complete knowledge of all information in the economy and who is charged with maximizing the welfare of the community.

- See Hayek (1945, p. 521).

- See Mankiw (2017).

- See Mankiw (2017). See also Taylor (2012, p. 1).

- The process is interactive, with market participants not only influencing prices, but also responding to price signals.

- See O'Driscoll (1977, p. 27).

- See, for example, Serrano (2002).

- For example, an article in the area of international trade noted (Bernhofen and Brown, 2004, p. 49): "The insight that prices contain the relevant information about underlying economic fundamentals goes back to the pioneering work of Hayek (1945)."

- See Friedman (1977, pp. 456–67). The notion that distortions to relative-price patterns lead the economy's output level to deviate from its natural value would be formalized by Woodford (2003). See Hayek (1945, p. 527), and, for Friedman's use of the analogy between inflation and static, see Friedman and Friedman (1980, pp. 17, 274).

- Shortly before he received the prize, Stiglitz (2000, p. 1468) noted that the 1945 Hayek paper recognized that "the central problem of economics was a problem of knowledge or information"—and so it anticipated the field of the economics of information. And in his Nobel lecture, Myerson (2008, p. 586) credited Hayek's "widely influential paper" with helping spur mechanism-design research—by characterizing alternative institutional frameworks as different mechanisms for "communicating widely dispersed information about the desires and the resources of different individuals in society."

- For example, while Stiglitz (2000) agreed that the price system is a means of collecting and transmitting dispersed information, he took issue with the notion that this system always produced the most efficient economic equilibrium. Specifically, Stiglitz argued that incomplete information could lead to unnecessarily high unemployment and other undesirable outcomes that could be improved on by government intervention. In a similar vein, Dasgupta (1980, p. 115) noted in response to Hayek's (1945) position: "It can immediately be argued that the fact that much information is private is not on its own sufficient to warrant the unfettered play of market forces to be judged the best possible resource allocation mechanism." Return to tex

- See Kohn (2009). See also Yellen (2017, p. 4).